“They called me and told me to make a decision right away, because my daughter was near death,” recalls Kathy about the day her baby girl was born in November 1995. Kathy never imagined her full-term newborn, Rachael, would need a life-saving therapy. If it worked, Rachael would be the first neonatal patient at UNC to survive as a result of ECMO.

“They called me and told me to make a decision right away, because my daughter was near death,” recalls Kathy about the day her baby girl was born in November 1995. Kathy never imagined her full-term newborn, Rachael, would need a life-saving therapy. If it worked, Rachael would be the first neonatal patient at UNC to survive as a result of ECMO.

When their daughter was born at Rex Hospital in November 1995, Kathy and Dale Schissler’s elation at the birth of their first child quickly turned to dread. Though born full-term, Rachael was struggling. Something was terribly wrong.

When their daughter was born at Rex Hospital in November 1995, Kathy and Dale Schissler’s elation at the birth of their first child quickly turned to dread. Though born full-term, Rachael was struggling. Something was terribly wrong.

Doctors soon determined the cause. Rachael was suffering from pulmonary hypertension—a lack of oxygen in her lungs—and her lungs were hemorrhaging as result of her breathing meconium (a baby’s first stool) while still in the womb.

“We knew that she had aspirated meconium, but we had no idea that it was as bad as it was,” says Kathy. “As new parents, we had no idea what we were facing.”

Doctors at Rex Hospital quickly realized Rachael needed more specialized acute care than they could provide and transferred her to the neonatal intensive care unit at UNC. When an experimental drug didn’t work, Kathy faced a tough decision, one she would have to make without the benefit of Dale’s input: a new therapy called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, better known by its abbreviation, ECMO, might help—but if it worked, Rachael would be the first neonatal patient at UNC to survive.

“They called me and told me to make a decision [about ECMO] right away, because my daughter was near death,” remembers Kathy. “My husband was on the way from Rex to UNC, and this was before cell phones, so I had to make the decision without him.”

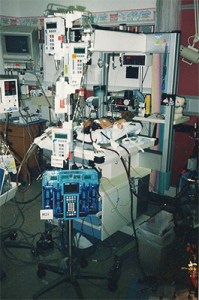

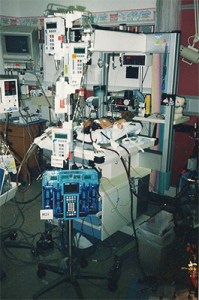

ECMO is now standard treatment for newborns with respiratory failure, but nearly two decades ago, UNC was new to the therapy, a form of cardiopulmonary bypass. An artificial heart and lung temporarily take over bloodflow, supplying oxygenated blood to the baby’s body.

ECMO is now standard treatment for newborns with respiratory failure, but nearly two decades ago, UNC was new to the therapy, a form of cardiopulmonary bypass. An artificial heart and lung temporarily take over bloodflow, supplying oxygenated blood to the baby’s body.

The proposition that Rachael would be a first terrified Kathy, but there was no time to waste. She gave her consent.

Rachael spent four days on ECMO, her condition quickly improving, and the Schisslers and Rachael’s care team became increasingly confident that she would survive. A couple of weeks post ECMO, the new parents took Rachael home, a moment celebrated by all her caregivers.

“We went back to see them, just to go up to the ward to say hello, when Rachael was three months old,” says Kathy. “They called everybody up to see her. They were so excited to see the success story.”

Since 1995, when Rachael was placed on ECMO, the therapy has saved the life of dozens of pediatric and neonatal patients at N.C. Children’s Hospital. During the most recent five-year period, from 2008-2013, about 70 Children’s Hospital patients were placed on ECMO, more than half of them saved as a result of the therapy.

From the time she was released from the hospital, Kathy says Rachael’s development was typical.  Now, 18 years later, Rachael is a senior in high school, applying to colleges and keeping busy as a healthy, active teenager. She’s a competitive soccer player and has helped teach the sport to children with special needs. She’s also on the sports medicine crew at her high school and hopes to one day become a pediatric physical therapist.

Now, 18 years later, Rachael is a senior in high school, applying to colleges and keeping busy as a healthy, active teenager. She’s a competitive soccer player and has helped teach the sport to children with special needs. She’s also on the sports medicine crew at her high school and hopes to one day become a pediatric physical therapist.

“Rachael is very well-rounded,” says Kathy. “We just feel really fortunate. She’s a great kid.”

And thanks to a life-saving experience that Rachael can’t remember, she’s developed a good perspective on life.

“Learning about her birth has made Rachael thankful that she’s gotten these experiences,” says Kathy. “It also makes her really interested in what she can do to help people.”