A new medical education building would help UNC train more doctors, and the UNC School of Medicine’s rural physician program is already training doctors to work far from urban centers.

A new medical education building would help UNC train more doctors, and the UNC School of Medicine’s rural physician program is already training doctors to work far from urban centers.

By Susan Hudson

Who wants to be a country doctor? That’s the question Robert Bashford, MD, has in mind whenever he meets prospective medical students. As associate dean for admissions at the UNC School of Medicine, Bashford is always on the lookout for potential rural doctors for the Kenan Primary Care Medical Scholars Program.

“He knows when someone has a rural heart,” said Hallum Dickens, a third-year medical student in the program. Dickens grew up in a low-income family in White Level, a rural community in Franklin County, and came to Chapel Hill originally as a Carolina Covenant Scholar. “People who come from underserved communities are more likely to return to practice there.”

The purpose of the rural physician program is to increase the number of Carolina medical students seeking health careers in rural and underserved areas in North Carolina and to retain them.

Funded by the William R. Kenan Jr. Charitable Trust, the program is a key component of the School of Medicine’s mission to not only educate doctors, but to get new doctors to set up practice in rural regions of the state where they are needed most, said William L. Roper, MD, MPH, dean of the UNC School of Medicine and CEO of UNC Health Care.

“What we have learned over time is the best predictor of someone’s likelihood of going to a rural area to practice is that they are from a rural area,” Roper said. “The way Dr. Bashford puts it, ‘It helps if they talk funny.’ He is talking about his strong Southern accent. But seriously, it helps a great deal to have family and other personal ties to far western or eastern North Carolina.”

To educate more doctors, the UNC School of Medicine plans to build a bigger, state-of-the-art medical education building, funded in part by $68 million from the Connect NC bond. The state’s voters will decide the fate of the bond at the polls on March 15.

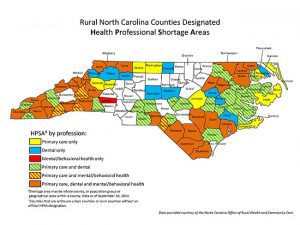

Less than 5 percent of physicians trained in North Carolina are currently practicing primary care in a rural county, according to a presentation made by the Sheps Center to a rural health task force.

“In 10 years, I hope we will have filled the gap in the underserved areas of the state, and we will have less people coming to the big hospitals for primary care,” Bashford said.

A commitment to rural medicine

The UNC School of Medicine made its commitment to improve the education and retention of rural physicians in 2013, when it launched the Kenan program, modeled after a successful program in Alabama. The program requires collaboration with the UNC School of Medicine-Asheville Campus, Mission Hospital in Asheville and MAHEC, the Mountain Area Health Education Center.

Students attend the first two years of medical school at Chapel Hill, then commit to the longitudinal program at the UNC School of Medicine-Asheville campus for their third and fourth years of medical school. They need to study one of the areas that the program classifies as “primary care”: family medicine, psychiatry, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics or emergency medicine.

Each medical student in the program also has a six-week summer internship in a 16-county region in western North Carolina, working directly with a local physician. In the last two years of medical school in Asheville, students work in rural hubs staffing clinics and doing rotations in rural areas.

“Of the 100 counties in North Carolina, 80 are considered rural. That’s a huge need,” said Amanda Greene, the Asheville-based director of the program. “Several counties don’t even have a hospital or an urgent care center. The patients have to be airlifted to a hospital to be treated.”

Meeting that need hasn’t been easy, Greene admitted. “It’s difficult to recruit students to work in rural underserved areas,” she said. They won’t make as much money to pay off staggering student loans, for one thing, and they may be the only physician in a 50-mile radius. If they’ve never lived in a rural area before, they may not be able to adjust to the relative isolation of life in the country.

The program has several approaches to keeping medical students interested in rural medicine. One is the monetary incentive of the scholarship that makes establishing a rural practice affordable.

Another is education, with extra classes designed especially for students headed to a rural practice, such as Appalachian culture, alternative medicine, ethics and health care disparities. Even after the students graduate, the program provides support in the form of continuing education on rural issues.

The program also provides experience. Students have many opportunities to interact with rural doctors and their patients during the school year and in a summer internship called the “Rural Experience.”

‘Pick the right people’

But the most important step is the first one: recruitment.

“Pick the right people. Pick the right people. Pick the right people,” Bashford said. He and his fellow evaluators have been very selective, offering scholarships to 24 students over the past four years.

“You’ve got to get kids with a rural heart. They’ve got to want to be in these places,” Bashford said. As soon as one first-year medical student Bashford met at orientation began telling him about his watermelon patch, Bashford knew that the watermelon-growing student was meant for the rural physician program. “And now he’s ours,” Bashford said. “And he’s brilliant.”

Another reason to choose the scholars carefully is that they aren’t under any legal obligation to go into rural medicine. They have to be genuine in their interest. “This is a handshake deal,” Bashford said. One student who is still struggling with a commitment to rural medicine hasn’t cashed any of her scholarship checks, just in case she changes her mind. “Now that’s genuine,” he said.

Ben Stepp, a family practice doctor who just joined the only medical office in Madison County, is supportive of the Kenan program to produce more rural physicians. “Hopefully, it’s a long term investment, not just in Western North Carolina but rural North Carolina in general,” he said.

Stepp, when he was practicing in Bryson City, was a preceptor for two of the Kenan scholars during their six-week rural experience internship. “The two students that I had, it was inspiring to them,” he said. “They were from more rural areas, so they knew what it was like. I think it made them more interested in primary care.”

More than a doctor

One of those students was Dickens, the Covenant Scholar mentioned earlier. After graduating in 2010, Dickens took a roundabout path to medicine, spending a year doing insulin-related research, then a few more years teaching English abroad in the Republic of Georgia and Argentina. The new program for rural physicians brought him back to Carolina. Here, in addition to his studies, he also worked with SHAC (Student Health Action Coalition), a student-run clinic, first as a Spanish interpreter and then as coordinator of the triage team.

“SHAC helped me remember why I was in medical school,” said Dickens, who has a particular interest in helping migrant farmworkers. This year, he is one of two Kenan scholars working in the rural training hub in Hendersonville, which has a large migrant population.

Some medical students may not want the rural life, he said, and he understands why. A heavy workload, isolation, run-down local economy and lack of educational opportunities for children are some of the drawbacks he mentioned.

But Dickens also remembers the family doctor he had growing up. That doctor started boys and girls clubs, raised money for a community swimming pool and began a nutrition initiative in the local school system. His wife served on the school board.

“My idea of being a rural physician definitely involves being a good citizen – being engaged and active in the community,” he said. “The community expects you to be more than just a doctor.”

Susan Hudson is the associate editor of the University Gazette, a publication of the UNC Office of Communications and Public Affairs.