Nicoleta Constantin is part of a generation of Romanians that found opportunities outside of Romania after the fall of communism. In her life in the United States, she has performed groundbreaking biochemistry research in the lab of Duke Nobel Prize winner Paul Modrich, but she found her calling when she became a pediatric nurse at North Carolina Children’s Hospital.

by Zach Read – zachary.read@unchealth.unc.edu

Anti-government protests broke out in the city of Timișoara, in western Romania, on December 16, 1989. Within days, they spread across the country, including to Bucharest, Romania’s capital, where Nicoleta Constantin was a student at the University of Bucharest.

Bucharest saw many instances of civil unrest during this period. In one incident, police and military forces surrounded demonstrators in University Square. When Constantin heard about what happened, she and a group of students and professors gathered at the biology department to “protect it.”

“We didn’t even know what we meant by ‘protecting it,’” says Constantin, who was majoring in biochemistry. “We just wanted to be involved, so we went to the biology department and talked all night, sharing stories and discussing the future of the country.”

The following morning, a few days before Christmas, Constantin walked home to her family’s flat. It was cold and eerily quiet on the streets. No traffic. No people.

“The city was frozen,” she recalls. “I was the only person out. As I passed the Ministry of War, I saw a burned-out vehicle and dead bodies on the ground. Through my studies, I was well acquainted with human anatomy and physiology. I noticed the layers of skin, fat, muscle, and bone on one particular body. It was very scary and very powerful. At that moment, it sank in how serious this was.”

A Generation that Left

In the years leading up to 1989, living conditions in Bucharest had deteriorated.

“It had grown progressively worse,” she says. “There were long lines for everything. Basic needs were rationed to the point where we had a strict schedule for heat, electricity, and hot water; we were limited in supplies like oil and sugar; we had time restrictions on watching television; and we were prohibited from taking pictures or even owning a typewriter because there was no freedom of speech or press.”

Circumstances were so bad in the 1980s that on winter evenings Constantin and her brother wore gloves while doing homework in their heatless flat. Despite the challenges, she was passionate about school, and her educational interests were varied. She had begun learning English in the second grade and French in the fifth grade, and for a long time she dreamed of being a foreign language teacher.

“People kept asking, ‘What are you going to do with foreign languages in Romania?’” she says, laughing about it today. “We didn’t have passports, so we couldn’t go anywhere – we couldn’t leave the country.”

By 1989, generations of Romanians were ready for change. The protests that began in Timișoara lasted for eleven days and became known as the Romanian Revolution. The period completed the fall of communist rule and marked the launch of democracy.

After the revolution, Constantin was part of the first generation of Romanians to have the opportunity to leave. In 1993, she chose to pursue her PhD in biochemistry at the University of Arizona. She had never left Romania, and didn’t know anyone where she was moving.

“I got on a plane and went,” she says. “On the other end, there was a nice couple from the biochemistry department waiting for me with a sign – on one side was a Romanian flag, on the other was my name.”

Hired on the Spot

The couple volunteered to host Constantin in their house until she was settled in Tucson and could figure out where to live. She worked in the lab of Mark Dodson, PhD, focusing on DNA replication in herpes simplex virus type 1. He was trying to understand how the virus assembles its DNA replication machine to find ways of disrupting it.

“I loved the troubleshooting and critical thinking involved in basic science research,” she says. “It was hard work, but there’s immense satisfaction in developing elegant ways of asking a question and then designing a clean experiment with controlled variables, devoid of noise. For me, there’s so much pleasure in that kind of discourse.”

While in Tucson, Constantin met fellow PhD candidate Bryan Arendall. The two began dating, and eventually married. As both were finishing their PhDs and searching for post-doctoral fellowship positions in labs across the country, Arendall met David and Jane Richardson, protein crystallography researchers at Duke University, at a conference in San Diego. He was offered a job.

“Duke hadn’t been on my radar,” says Constantin. “I’d interviewed at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and other universities, and my initial reaction was, ‘No way – I’m not going.’ But I spoke with my PhD advisor and asked, ‘If I were to go to North Carolina, is there anyone in the area you know who would be interested in my work?’ He said he knew someone at Duke named Paul Modrich, who was studying DNA repair, a very close relative to what we were studying in Arizona. And he said that Paul was great.”

Constantin didn’t know if Modrich was in need of postdocs, but she reached out to him and asked if she could share her work with him when she and Arendall were in Durham. Modrich agreed.

“I presented my work and he hired me on the spot.”

Modrich Lab

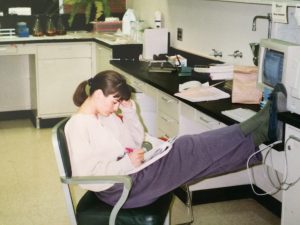

Constantin worked in Modrich’s lab from 2001 to 2006. By the time she arrived in North Carolina, the lab had already succeeded in reconstituting bacterial DNA repair in vitro and was carefully searching for the factors involved in human DNA repair. A next step for the lab was to reconstitute DNA repair in the human system – an accomplishment that would pinpoint the molecules involved in maintaining DNA stability in normal health as well as those involved in DNA instability during diseases such as cancer. Constantin’s work in Arizona had prepared her to contribute right away.

“I already had experience in purifying proteins,” she says, “so my experience merged beautifully with the questions Dr. Modrich was asking, and we were able to take DNA containing a mistake and correct it in a cell-free solution, in a tube.”

Early on in Modrich’s lab, Constantin noticed a level of intensity that she had not seen out west, where she found it more easygoing and less competitive. Although the Duke experience was more intense, the competition, she explains, was healthy.

“It was collaborative,” she says. “We were competitive with each other, but in a good way. At times, it could be very intense because you have eight to 10 determined and passionate scientists trying to discover things and working together on similar projects, but that’s natural. It was also a great environment for troubleshooting because every few weeks we presented our data and findings to Dr. Modrich and each other, a group of highly critical thinkers. The critiques helped us know if we were on the right track or what pieces were missing.”

Constantin credits Modrich for fostering an atmosphere of scientific discourse that didn’t make his postdocs feel they were being criticized when being critiqued.

“Enthusiasm and curiosity were necessary tools in the lab,” she says. “You had to be smart, you had to study, and you had to work hard. Dr. Modrich always required high-quality work, and nothing left the lab – nothing was published – until it had been fully developed and cross-checked. It had to be pristine. I love pristine work.”

Modrich recalls Constantin’s impressive skills as a scientist.

“She’s extraordinarily talented,” Modrich explains. “Experimentally, she was outstanding – a very gifted experimentalist. She could see what path her experimental work should follow, and she was very talented technically, so her experiments had a high probability of working.”

In addition to her scientific contributions, Constantin had a positive influence on morale.

“Labs can be tough places,” Modrich continues. “Personalities can sometimes clash. But she is a delightful person and was always positive. There are two kinds of people in labs: those who prefer to work by themselves and those who tend to work together. I let people choose their own path. Much of Nicoleta’s work was done with several other people, and I think that has to do with people liking and respecting each other. The relationships she was able to form helped her be very productive.”

A Calling

As a student at the University of Bucharest, Constantin taught English to six-, seven-, and eight-year-olds at the Waldorf School. Waldorf education had just been introduced in Romania, and the school needed an English teacher. The parents of a student she was tutoring recommended her.

“I knew I loved kids even then,” she says. “It was the best. I loved teaching; I loved nurturing.”

A few years into working in DNA repair at Duke, she began looking for ways to relieve lab-related stress. She missed interacting with children and felt that a nurturing side of her had been neglected. She decided to volunteer at Duke Children’s Hospital & Health Center, which was located near Modrich’s lab.

For two years, Constantin went to the Duke Children’s Hospital & Health Center after finishing her day in lab to coordinate and escort therapy dogs and their handlers to visit pediatric patients. Witnessing firsthand the interactions between caregiver and patient opened her eyes to the role nurses play in the lives of patients and their families.

“I began thinking about how long it takes for bench science to impact patients,” she says, “and I wanted to be involved in improving the lives of patients more immediately. Plus, being around kids and dogs was heaven for me. That told me that I want to do this – that I want to be around this somehow. I have this image of a nurse coming out of the hospital as I was going in, and it stays with me today. I’ve always been drawn to nurses because in my mind a nurse is clear, focused, and smart, and they save lives. I wanted to do that.”

At the time, Constantin was coming to the end of her postdoc period and facing the prospect of making a career in basic science research in an academic setting or pursuing industry work.

“For me, this was a period of self-discovery – of soul searching,” she says. “Being around these children, seeing the care that was being provided to them and the relationships that nurses form with their patients, compelled me to pursue it.”

In 2006, Constantin decided to leave research and get her degree at the UNC School of Nursing. Modrich was both surprised by her decision and happy for her.

“Maybe I was a little disappointed,” he laughs, “because I thought she was very talented. But she started volunteering with pediatric patients at Duke while working in my lab, and she just fell in love with it. I’ve always believed that people should follow their hearts. You spend many of your waking hours in your profession, so it should be one that you truly love, and I know that she loves what she’s doing now, so she made the right choice.”

Nurse Educator, Nurse Scientist

In nursing school, during her pediatric rotations, Constantin discovered 6 Children’s, a pediatric unit at North Carolina Children’s Hospital. 6 Children’s is a general medicine floor, which means it serves pediatric patients with a wide range of chronic neurological, gastrointestinal, endocrine, and renal conditions; genetic diseases like cystic fibrosis; metabolic disorders; and other serious conditions. She enjoyed her rotation on the unit so much that she applied to work there upon graduating from nursing school in 2007.

“I never considered anything but pediatrics,” she says. “Then, when I found the nurses on this unit so helpful, so open, and so nurturing in interactions with kids and families, I knew this was where I wanted to be.”

From the moment she joined the unit, it was clear that Constantin had a skillset that could be applied to nursing education. Sheryl Galin, the unit’s nurse manager, a nurse at UNC Hospitals for 30 years, and a graduate of the UNC School of Nursing, has hired nurses who were engineers, came from research backgrounds, and had higher degrees including MAs and PhDs, but she had never come across a nurse with Constantin’s set of experiences.

“Nicoleta has a very unique way of looking at patients,” Galin says. “She’s able to see patients in a truly holistic way – not only in terms of providing care, but in understanding what’s going on inside the patient from a physiological standpoint, how the medications work, and why they’re being administered.”

6 Children’s is North Carolina’s referral center for pediatric patients with metabolic disorders. Muge Gucsavas-Calikoglu, MD, MPH, associate professor of pediatrics at the UNC School of Medicine, specializes in pediatric genetics and metabolism. She estimates that 75 percent of children with metabolic disorders in North Carolina who need inpatient services are treated through the unit.

“Metabolic disorders are chronic, complex conditions that require intensive management,” says Dr. Gucsavas-Calikoglu. “Nicoleta took over nursing education from me and has been instrumental in helping our nursing team understand the needs of children with these rare disorders. Today, because of Nicoleta, we have an environment that is an excellent place for nurses to learn about caring for these patients.”

According to Dr. Gucsavas-Calikoglu, Constantin’s efforts have brought together attending physicians, residents, and nurses so that everyone is on the same page when it comes to care of metabolic disorder patients, and the result has been even better patient care.

Galin agrees that Constantin’s educational efforts have helped speed up the understanding of metabolic disorders among nurses.

“The disorders are complex, there are a lot of them, and they can be challenging to understand, but Nicoleta teaches us the most complex things in an easy-to-understand format, so when she’s done, you understand it,” says Galin.

Today, Constantin publishes educational newsletters and conducts lecture series for her colleagues on the unit. Meanwhile, she has also pursued research projects. In 2012, she became one of the inaugural UNC Hospitals-endowed Becton-Dickinson fellows, earning a grant for bedside research that could reduce the frequency that patients with cystic fibrosis have to be stuck with needles when measuring antibiotic levels. The project required her to enlist other units to participate, train nurses on those units to draw labs following the same protocol to minimize variability, and even come to work when not scheduled if there was no one available who was trained to draw labs for the project.

“A Moment of Caring”

At the heart of Constantin’s work at UNC Hospitals is her commitment to building relationships with patients and their families.

“She has the scientist part of her brain for education and research and the caring side of her brain for building relationships with families,” Galin says. “She spends so much time with her families and really commits to those relationships.”

In fact, Galin laughs when looking back at Constantin’s initial year as a nurse, when the unit had a hard time prying her away from her patients.

“At the beginning, she wanted to spend so much time with families – sitting down with them, talking with them, and learning about them – that she would sometimes get behind,” Galin says. “We’d tell her that she had to keep moving, and she’d say, ‘I know, but I want to know how their family works – I want to understand them better.’ Today, she’s learned how to balance those two things: building relationships with families and applying the scientific skillset she has.”

According to Galin, Constantin has also mastered “A Moment of Caring,” a key element of UNC Health Care’s patient care delivery model, Carolina Care®.

“Our nurses form wonderful relationships with our patients and their families,” Galin says. “Nicoleta is the kind of person that – even if it’s a patient we may never see again – can tell you everything about the patient because she really emphasizes these ‘moments of caring.’ She takes time to learn about her patients and their families. She wants to know who the patient is, who their favorite friend at school is, what they enjoy most at school. Nicoleta is one of our many great nurses, but the way she builds relationships is definitely unique.”

Dr. Gucsavas-Calikoglu admits that when she became a physician, she did not expect to collaborate with a nurse with Constantin’s career path.

“She is able to teach others so effectively about such complicated material,” Dr. Gucsavas-Calikoglu says, “and in addition to teaching and research, she’s very caring. She treats these kids like her own. It’s not only the scientific part, but the human part that takes priority in her care.”

The Nurturer and the Researcher

While Constantin and Arendall were in Arizona, Arendall was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He was only 41 at the time. Constantin believes it subconsciously played a role in her decision to go into nursing.

“I probably wanted to learn more about how to help a person who’s chronically and degeneratively ill, so I’m sure that factored in,” she says. “I realized that I didn’t need to be with viruses and bacteria all the time – I needed to be with people.”

After the diagnosis, it was tempting for Constantin and Arendall to apply their skills to Parkinson’s research. Both decided they are too emotionally connected to the disease to be confident that they could be objective scientists.

Instead, they keep updated on the new research and new clinical trials on a daily basis.

“My past as a researcher has been helpful with coping with Bryan’s illness, with feeling that something can be done about it,” Constantin says. “I am really hopeful for a cure.”

Although she is no longer in basic science research, her contributions in Modrich’s lab continue to be felt today. In October, Modrich was one of three winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, along with UNC School of Medicine’s Aziz Sancar and London Francis Crick Research Institute’s Tomas Lindahl. Constantin’s work was acknowledged by the Nobel committee among the other important discoveries in Modrich’s lab, so she was on hand in Stockholm, Sweden, for the Nobel ceremony in December.

“She sent us pictures of the dresses she was picking from for the different events she was attending during her trip,” says Galin. “She asked all of us on the unit to vote for our favorite. We were all so excited for her.”

Reflecting on the trip several months later, Constantin remains in disbelief.

“I get goosebumps to this day because, as Alfred Nobel has put it, the Nobel Prize is ‘awarded for the greatest benefit to mankind,’” she says. “When you are even remotely associated with this phrase it gives you chills. For me to be involved in any way is still unbelievable.”

Constantin maintains close relationships with Modrich, his wife, Vickers Burdett, who is also a researcher in his lab, and other former colleagues from the lab. In fact, when she sees Modrich and Burdett, Burdett has often knitted blankets for Constantin to take back to the patients and families on 6 Children’s. Constantin admits that she misses the rigorous intellectual exercises of working in a lab of Modrich’s quality, but she continues to feel that she made the right decision by going into patient care.

“If I am grateful for one more thing in choosing this career it is that I learned to cope,” she says. “It is not easy to be sick or to take care of a sick person. There is a lot that goes into doing that job emotionally, physically, and intellectually. A lot of the children and families we care for on 6 Children’s are struggling with these conditions in their daily lives, and many have lifelong illnesses. I’ve been able to connect with them and share empathy because I’m a caregiver myself. Going into nursing turned out to be a great decision in my life because it is who I am completely: the nurturer and the researcher.”