UNC medical student Yousef Abu-Salha fulfilled a dream of caring for child refugees from Syria, while honoring the legacy of his slain sisters Yusor and Razan and best friend Deah — Our Three Winners.

by Zach Read – zachary.read@unchealth.unc.edu

With a view of the border wall that separates Turkey and Syria in front of him, UNC medical student Yousef Abu-Salha pulls up a chair at a makeshift dental and medical clinic to talk to a child from Syria, a refugee orphaned by war. She is a student at Al Salam School – or School of Peace – in Reyhanli, Turkey, where the clinic has been arranged in an outdoor classroom. Her left leg bears a long scar, perhaps the result of shelling that occurred in her community, before her family fled Syria.

Yousef notices that she is quiet, reluctant to open up. As a member of Project Refugee Smiles, he understands that he and the team of dental and medical students and professionals might be viewed skeptically by this population of patients, which has endured so much pain, for so long. He pulls out a large green dragon head with an enormous set of teeth, given to him by a friend from Raleigh who traveled with Project Refugee Smiles one year earlier. Speaking in Arabic to her, he uses the dragon to demonstrate proper brushing and flossing techniques. He feels close to her – as if she’s his own family.

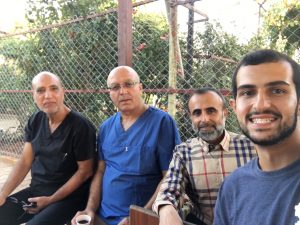

This summer Yousef was one of two dozen dental and medical students and professionals who were part of the international relief effort to provide care to child refugees from Syria. They performed fillings and extractions, taught preventative medicine and dental-care techniques, and offered acute dental and medical care for hundreds in need at Al Salam. For refugees of the war in Syria, such access to health care is anything but typical.

“Providing these services for Syrian refugees at Al Salam was the dream of Deah, Yusor, and Razan,” says Yousef, the older brother of Yusor and Razan Abu-Salha and the best friend of Yusor’s husband, Deah Barakat. “They were so passionate about helping these children.”

Deah, Yusor, and Razan are remembered throughout the United States and the world, including by children and staff at Al Salam, as the three young Muslim Americans who were senselessly murdered in Chapel Hill in February 2015. As the world learned more about them, they became widely admired as caring young people who had already accomplished many great things in their far-too-short lives. Deah, Yusor, and Razan became the inspiration for Our Three Winners, an endowment dedicated to support the philanthropic causes, both locally and globally, that were their passion.

“In 23, 21, and 19 years, respectively, it’s almost like they lived a thousand years,” says Yousef, who is now a second-year med student. “It’s amazing how much they did for people. Deah and Yusor went on relief trips to the West Bank and Turkey, and Razan worked tirelessly to feed the homeless in downtown Raleigh. Razan’s dream was to utilize her background in architecture to build playgrounds for children in African countries — I hope to fulfill that dream for her.”

Now Yousef is walking and working in their footsteps while learning to become a doctor with a heart focused on serving his communities in North Carolina and abroad.

The Cause

Reyhanli, near the Mediterranean coast and along Turkey’s southeast border with Syria, is a mere 45-minute drive from the Syrian cities of Aleppo and Idlib. It has become a safe place for refugees fleeing the five-and-a-half-year conflict – a crisis that has taken the lives of more than half a million Syrians, according to the Syrian Center for Policy Research.

For the past two years, Project Refugee Smiles, organized by the Syrian American Medical Society, has run a weeklong summer clinic at Al Salam, where nearly 1,900 Syrian refugees attend school. Founded by Syrian-born Canadian pharmacist Dr. Hazar Mahayni, Al Salam offers education – and at least some sense of normalcy – to Syrian children who have been displaced by war and are living in nearby refugee camps.

“Many of them have lived in these camps for most or all of their lives, since the war began more than five years ago,” says Yousef. “All they know are these conditions, yet they welcomed us and were so excited to have us there.”

In February 2015, Deah, Yusor, and Razan were raising money for the inaugural Project Refugee Smiles trip, which was to occur several months later, during the summer. They had been attracted to Al Salam because of Dr. Mahayni’s vision to organize the school around one central idea: “Education is even more important than food.”

“Education as a vital human right and powerful tool in the fight against these circumstances is the mission of the school,” explains Yousef. “When the principal first met these children, many wanted to go back to Syria to be martyrs in the ongoing conflict – to be like their beloved family members who innocently died in the war. Today, thanks to the education they are receiving, they want to live and contribute in a better way.”

Using his medical training, Yousef triaged patients, took medical histories, gave general physical exams, and provided services for children with minor medical issues. Fluency in Arabic allowed him to communicate freely with the children and their parents or guardians, and in five clinic days Project Refugee Smiles saw roughly 400 patients, whose resiliency astonished the group.

“Our first day there I was in awe of these children,” marvels Yousef, who was joined on this trip to Turkey by Deah’s sister, Suzanne, a UNC School of Medicine graduate and now a resident in San Francisco; Deah’s brother, Farris; and Deah’s mom, Layla. “The kids were so happy to have us. They were singing for us and drumming for us and welcoming us with open arms. In a short amount of time, I felt that we connected with a lot of them on a very personal level.”

Making Them Proud

As an undergraduate, first at NC State and then at UNC, where he transferred, Yousef was interested in dentistry and medicine. He shadowed professionals in both fields, and late in his undergraduate career, during his final semester, he took biochemistry, anatomy, and physiology.

“That sealed the deal,” he says. “After those courses, I decided to go to medical school.”

Most of his peers who were going to medical school had already been accepted to their programs and were enrolling in the summer. Yousef’s late start meant he’d have to wait more than a year to begin his medical education. Rather than delay his learning, he started school at the American University of Antigua (AUA) in the Caribbean.

He completed three semesters of basic sciences, and after celebrating Yusor’s and Deah’s wedding, he returned to the Caribbean for his fourth semester. Shortly after he resumed classes, the unimaginable occurred in Chapel Hill: his sisters and best friend were murdered in their apartment by a neighbor.

“We’d had such an incredible winter break celebrating their wedding,” Yousef recalls. “In addition, Yusor had a birthday, she’d just graduated from college, and she’d been accepted into dental school at UNC, where Deah was studying. It was a wonderful time. I flew back to Antigua on February 1st for what would have been my final semester before taking the boards and starting rotations in the States. I returned from Antigua 10 days later, on February 11th,” one day after Deah, Yusor, and Razan were killed.

After the tragedy, Yousef took a leave from medical school to be with his parents, Mohammad Abu-Salha, MD, a psychiatrist in Clayton, North Carolina, and Amira Bamyeh, a pharmacist who manages the family’s Clayton clinic. While at home, he looked into the possibility of continuing his medical education at UNC, closer to his family. He earned an opportunity to do so in the summer of 2015, but rather than pick up his course work at UNC where he left off at AUA, he opted to start his medical education over.

“The curricula between the two schools are very different, and although it was possible to sync my previous coursework with UNC’s, it would have been challenging for me at that time,” he explains. “I wanted to have the flexibility in my schedule to take care of my family.”

At UNC, Yousef has felt welcomed and supported by classmates. Last year, his peers organized a fundraiser for the Our Three Winners endowment, and in February 2016, on the anniversary of the deaths of Deah, Yusor, and Razan, many of his classmates traveled to Raleigh to be at his side at a vigil held at NC State for his family members.

“It was an intense study time during medical school,” he notes, “so I was extremely touched that my classmates made that effort. It meant a lot to me. I think most if not all students know my family’s story, but they treat me very regularly, very normally, and with a lot of courtesy.”

The same is true of all the deans at the School of Medicine.

“They are wonderful,” Yousef says. “I will forever be grateful to them, and I want to make them proud.”

Finding a Mentor

In April 2015, before starting coursework at UNC, Yousef reached out to Dr. Richard Feins, Professor of Surgery and Medical Director of Perioperative Services, about joining his lab. Feins, a cardiothoracic surgeon by trade, runs a lab that specializes in surgical simulation.

“It was soon after our tragedy, and I was still trying to heal, gain traction, and move forward positively,” Yousef recalls. “I was looking for a summer job prior to starting school at UNC in August. He allowed me to work in his lab, and it has been a wonderful experience.”

Over the last year and a half, with the help of Feins and the lab, Yousef has developed four simulators for performing tracheotomies and placing tracheostomies, as well as a simulator, developed with the Department of Urology, to practice dissecting abdominal lymph nodes for testicular cancer and other medical cases. The tracheotomy simulators will be used at Area Health Education Centers across North Carolina while educators in Chapel Hill use telesimulation technology to monitor their work. Eventually, these simulators may be a sustainable way to train surgeons in developing nations, which dovetails with Yousef’s interests in serving underserved populations around the world.

Since Yousef arrived in the lab, his intelligence, dedication, and creativity have impressed Feins.

“Very early on it was readily apparent how talented he is,” says Feins. “He thinks a problem through, comes up with the solution, and then delivers the solution. We don’t like to be proscriptive in this lab. We believe in giving our researchers space to be creative to accomplish their goals. I have been so impressed by how productive he’s been. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen someone produce as much as quickly as he has.”

Yousef credits Feins, whom he calls a mentor and an inspiration, with his success in the lab.

“He encourages me to strive to reach my full potential,” Yousef says. “He also empowers me by testing my creativity, independence, and resourcefulness. I have learned much about surgery, craftsmanship, and academia from Dr. Feins.”

Perhaps most importantly for Yousef, Feins has treated him like every other medical student.

“Believe it or not, we only recently spoke about my story and my past,” says Yousef. “When I first met him, I was in too much pain to talk about it. It was important for me that he treated me like a normal medical student and gave me a unique research opportunity. I thank him for that. I’m sure to him what he did is a given. But it is all priceless to me.”

Feins’s admiration for Yousef has only grown as he has gotten to know him better.

“Yousef and his family have suffered unimaginable loss, and there are many paths someone in Yousef’s position could take after what he’s been through,” says Feins. “He’s chosen to help people and to honor those he has lost. That says so much about him and his character, and he has taught me so much.”

Love is Greater Than Tolerance

In 1990, Mohammad Abu-Salha and Amira Bamyeh, the parents of Yousef, Yusor, and Razan, fled Kuwait during the Iraqi invasion. They resettled in Jordan, and eventually moved to Virginia Beach, where Abu-Salha specialized in psychiatry at Eastern Virginia Medical School. Four years later, their careers brought them to North Carolina, where Abu-Salha worked on behalf of several of the state’s eastern counties. After years practicing at Johnston Health, now part of UNC Health Care, he and his wife opened their own practice in Clayton.

After the deaths of their daughters and son-in-law, Abu-Salha and Bamyeh took less than a month off of work before returning to see their patients.

“As parents, we were not in any way, shape, or form ready to go to work after our tragedy but for the fact that we decided to survive with faith and dignity despite our immense pain,” says Dr. Abu-Salha. “Our strength came from the Islamic belief in a plentiful reward from Allah – Arabic for God – for enduring the loss of our children. We follow the example of all Abrahamic prophets who practiced the same patience after their own losses and tribulations.”

Yousef reflects on how his parents have served as examples to him since the tragedies.

“My dad said, ‘I have a lot of patients that need to be seen,’” Yousef remembers. “Their strength and resilience were an inspiration to me. Even the night of our tragedy, when you would expect my dad to be taken care of, he was the caretaker of many grieving people during that time and for a long time afterwards. My parents have responded to hate with love, and they are channeling their negative emotion into positivity and overcoming unbelievable circumstances to continue helping other people.”

Their example has taught Yousef much about how he hopes to care for and support others. The compassion they demonstrate in all areas of their lives guide his approach to medical education at UNC, where he has found a likeminded institutional emphasis on serving underserved populations, both at home and abroad, and to becoming a doctor.

After returning from Turkey, Yousef has begun the formal process of serving as an interpreter for Arabic-speaking families navigating serious health challenges at UNC Hospitals, and since December 2015, he has served as co-leader of the UNC School of Medicine’s chapter of Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). Last semester, Yousef and PHR co-leader Nicole Damari, also a second-year medical student at UNC, attended a seminar at Georgetown University to learn how to medically evaluate refugees and asylum seekers. Yousef and Nicole have since organized educational sessions for fellow classmates on human rights in medicine, with special emphasis on refugee populations.

“When asylum seekers come to the United States, they need medical attention and medical evaluations to make their case,” Yousef says. “It’s a very sensitive population – they’re often very vulnerable and very scared because of what they’ve been through.”

The morning after returning from Turkey, Yousef traveled with Nicole to Greensboro, where they met Dr. Jeff Walden of Cone Family Medicine. Walden, an assistant professor of family medicine at UNC, oversees a Refugee Clinic in Greensboro. As part of this clinic, he administers N-648 evaluations, which medically evaluate disabled refugees in their quest for U.S. citizenship. In partnership with Elon Immigrant Law Clinic and the Cone Family Medicine Refugee Clinic, students from the UNC chapter of PHR helped create a specialized N-648 clinic. The N-648 clinic seeks to address the backlog of refugees in need of medical evaluation in the Triad and Triangle areas through a mobile medical-legal clinic that recruits and trains medical students to evaluate refugees, document and present to physicians, and work with physicians to complete the N-648 Medical Certification for Disability form, which is required for disabled refugees to be exempt from the civics exam.

“The problem for this diverse Greensboro-area patient population with refugee status from Vietnam and other countries is that they have disabilities and illnesses, yet have limited access to physicians willing to evaluate them and complete the form,” says Yousef. “This is a significant barrier for them, so with a backlog of some 150 patient cases, we saw patients, got full histories, examined them, spoke with them about the traumatic things they’ve been through, and submitted our findings to Dr. Walden. There’s an immense need not only for medical services, but for all kinds of services, for all kinds of populations in North Carolina. This is one of those populations.”

Yousef hopes to have more opportunities to work with refugee populations and to share his experiences with others, including medical students who may one day encounter these patients. But his larger goal is to show how these volunteer actions – like those undertaken so often by Deah, Yusor, and Razan – can change how we think about vulnerable populations.

“I want to see our society move past tolerance of minorities and other peoples and towards real integration, respect, and understanding of all,” he says. “We all have beautiful, diverse backgrounds and multifarious identities. Tolerance of each other is not adequate. You tolerate things that annoy or bother you. Instead, we must care about each other’s wellbeing. Using action – actually helping people – rather than trying to argue someone into being accepting of others, can help affect the change I dream of seeing. When you see, meet, and help people, you realize that we’re all the same.”

Two Girls

Last winter Yousef hosted three 3-on-3 basketball tournaments to benefit the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF), a group that provides nonpolitical humanitarian aid to children in Palestinian territory. The events, along with several races he ran in Razan’s honor — Razan was the runner in the family — raised more than $15,000 for PCRF. The funds will go toward building Gaza’s first pediatric oncology center.

“Deah would have loved the tournaments,” Yousef says about his longtime companion at Triangle-area gyms. “Basketball meant so much to him. He was really, really good, and I’m going to miss running the courts with him.”

Yousef also misses his thoughtful and selfless sisters. He keeps a heartfelt card Razan sent to him about his pursuit of becoming a physician.

“The words she wrote on the card are from our Prophet,” he says. “They include: ‘The superiority of the learned man over the devout worshiper is like that of the full moon to the rest of the stars (i.e., in brightness).’ They express our faith’s emphasis on the importance of expanding one’s knowledge and devoting one’s self to education. She felt inspired by my educational path – medicine – and said that it moved her toward action in her life.”

Today, weeks after returning from the Project Refugee Smiles relief trip, Yousef is hopeful because of his interactions with the refugee children Deah, Yusor, and Razan wanted to help. Two girls, in particular, remain close to his heart: sisters named Salwa and Layla. Salwa is eight years old, with big black eyes, black hair, and very tan skin. She is tall for her age. Yousef describes her as shy, perhaps stoic in the face of horrifying experiences.

“She had a big scar on her left leg, which made me wonder what she had been through and what she had witnessed,” he says.

Layla is six years old, small, a little frail, and fair-skinned. She is more happy-go-lucky than her older sister.

Both girls dressed nicely, in their best clothes, when they visited the clinic.

“So many children who came to the clinic were dressed formally,” he remembers. “To me, it was representative of their intact dignity even in the midst of unimaginable tribulation.”

To lift the spirits of their patients, Yousef and an orthodontist on the trip went to a nearby shop that sold a variety of goods, including toys. They bought out the entire toy section and gave toys to the children. Salwa accepted her gift but didn’t smile; Layla was immediately excited.

“These kids were not like the children I know in the States, including my own cousins,” Yousef says. “They have concerns that they carry with them and that show on their faces – especially those like Salwa, who were a little older and had experienced more. They didn’t seem to take anything for granted. Visits to the clinic meant a lot to them.”

Many of the children exhibited signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. Many had lost both parents in the war and attended the clinic with a guardian.

“I thought Salwa and Layla were with their mother,” says Yousef, “and in Arabic I asked them to call the woman who came with them over for me so I could speak with her. The woman came over, pulled me to the side, and said, ‘I just want to tell you that these girls are very special. Both of their parents died during the shelling in Syria. I am their grandmother.’ It immediately made sense why Salwa had trouble opening up to me.”

As they talked, Yousef explained that although he couldn’t relate to what they’ve been through, he understood the traumatic loss of family. He pointed to the big banner hanging in the clinic. On it was the image that has become so well known around the world: the black outlines of Deah’s hair and ears and Yusor’s and Razan’s hijabs. “Do you know who they are?” asked Yousef.

“Yes,” she answered. “Those are the three students who were killed in the United States.”

“They are my sisters and best friend,” Yousef said, his eyes welling with tears.

The grandmother immediately began to pray for Yousef.

“To have someone like their grandmother, who is experiencing circumstances I cannot imagine, pray for me, was very moving,” he says.

For Yousef, the journey was one of many he hopes to make in honor of Deah, Yusor, and Razan, so long as there are children in need like Salwa and Layla.

“My intention was to walk in their shoes and to see what Yusor saw when she was in Turkey in 2014,” he says. “I wanted to connect with these people that I’d only read about or seen on the news.”

Dr. Kahtan, a Syrian dentist who led the Project Refugee Smiles trip in Reyhanli this summer, worked with Yusor in Kilis, Turkey. He brought Yousef closer to Yusor’s experiences one night when he recollected to the whole team what it was like to work alongside Yusor and how she contributed to the mood of his clinic.

“He described her in Arabic, and it was almost poetic,” says Yousef. “It’s really hard to translate it into English, but what he was saying was so beautiful that I was sobbing.”

Sometimes, Yousef says, he feels numb to the personal losses because they are so ever-present in his mind, but Dr. Kahtan’s words served as yet another reminder of how much his sisters and Deah accomplished – and how much more they would have done to aid others had their lives not been cut short. It makes him cherish the Project Refugee Smiles trip.

“In our short time there, I could see that Al Salam was helping these children,” he says. “The children were able to connect with all of us, despite their circumstances. Dr. Mahayni’s goal is to give the children like Salwa and Layla a reason to live – to give them a chance to become girls not unlike my own sisters, dedicated to love of and service to others.”

Interacting with Salwa and Layla and their grandmother – and with all the people he and the Project Refugee Smiles team had the privilege of meeting during the trip – will not be forgotten by Yousef and the relief group. Nor will it be forgotten by the children and the school’s founder and first principal, who threw them a party of thanks before they returned home. But rather than say goodbye to the children and staff on their final day at the clinic, Yousef and the relief group used the parting phrase they’d come to learn from all the refugees whose lives and experiences had touched them and who refuse to give into hate – a phrase that carries a weight much greater than goodbye: “We’ll meet again in a free Syria.”