UNC Lineberger researchers led two major projects to mark the finale of The Cancer Genome Atlas project, which was backed by the National Cancer Institute and National Human Genome Research Institute.

UNC Lineberger researchers led two major projects to mark the finale of The Cancer Genome Atlas project, which was backed by the National Cancer Institute and National Human Genome Research Institute, and were involved in gene expression analysis since the beginning.

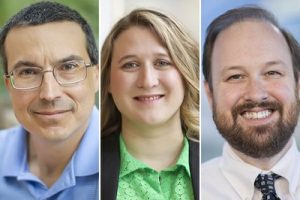

“UNC Lineberger played a pivotal role in the TCGA project since its beginnings in 2006, including serving as the site for gene expression profiling and analysis throughout the lifetime of this prominent national project,” said UNC Lineberger’s Charles M. Perou, PhD, the May Goldman Shaw Distinguished Professor in Molecular Oncology, a professor of genetics, and the co-leader of UNC Lineberger’s efforts in TCGA. “These final studies that are now being released represent the culmination of more than a decade’s worth of work, and are based upon the cumulative findings coming from 10,000 different human tumors.”

D. Neil Hayes, MD, MPH, formerly of UNC Lineberger and now at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s West Cancer Center, said the project has shown that genetic sequencing, like other technological advances in medicine, evolves over time. First, scientists had to wrestle with the technology itself, and then interpret the findings.

Eventually, the findings transition into common clinical practice. Ultimately, he said the TCGA project reflects that cancer is a disease of DNA.

“Every cancer cell has some DNA abnormality, and we now have the ability to assess this directly for the first time,” said Hayes, who is the Van Vleet Endowed Professor in the Division of Medical Oncology. “A direct assessment of the broken DNA of cancer will likely be a key step on the path to the treatment of many patients. The exact path may be different depending on the particular abnormalities in different diseases. Efforts such as the pan-cancer analysis are key papers in deciphering these abnormalities to translate into patient care.”

One of the major culminating efforts of TCGA Network researchers was an analysis of thousands of tumors to classify them according to their immune responses. Using genomic analysis, the researchers evaluated many distinct immune system features of a tumor at once, and were able to identify large groups of tumors that shared common immune cell features that were also shown to predict patient outcomes.

Benjamin Vincent, MD, UNC Lineberger member and assistant professor in the UNC School of Medicine Division of Hematology/Oncology, was co-corresponding author of the study published in the journal Immunity.

The study was one of 26 papers that were published the week of April 2 as part of the finale of TCGA. The project involved a collaboration by several hundred researchers, a major financial investment by the National Cancer Institute and National Human Genome Research Institute, and more than a decade’s worth of effort.

The researchers intend to leverage the findings to conduct further studies to see if the subtype groupings are linked with outcomes for treatments that use the immune system to fight cancer, as well as to identify biomarkers to help identify patients who will respond to other types of cancer treatments including chemotherapeutics.

“The biggest surprise to me from this effort was that there were a finite number of subtypes of cancer that span multiple tissue types,” Vincent said. “UNC Lineberger investigators are working to translate these findings into prospective clinical trials, and cutting-edge biomarker development.”

UNC Lineberger’s Katherine Hoadley, PhD, assistant professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Genetics, was lead and co-corresponding author of a study that analyzed 10,000 tumors, across 33 different human cancer types (i.e. breast, lung, colon, ovary). The researchers, who identified an expanded classification for cancers based on their genetic and genomic alterations, reported in the journal Cell that many tumors are very similar to each other based on these molecular features that reflect the cell type of origin, in some cases beyond similarities based upon a common anatomic location.

As a whole, TCGA has helped create a dictionary of alterations in cancers that other researchers can use to aid future efforts to better understand individual tumor types, the function of specific mutations, and other types of genetic abnormalities seen in cancer, Hoadley said. The data is publicly available, and next to data from the Human Genome Project, the TCGA data likely represent the most widely utilized human genomic resource.

“Having this catalogue of alterations in cancer will help guide future research, it will lead to a better understanding of how these alterations, and relates to outcomes for patients, which is why we made this data publicly available,” Hoadley said.

“The work of Dr. Hoadley and her colleagues on tumor subtypes, and of Dr. Vincent and colleagues on immune system-based subtypes, each represent a new classification system that is likely to make an impact in the cancer clinic,” Perou said.

“Along with the Human Genome Project, this is an example of a significant collaborative group effort driven by the National Cancer Institute,” Vincent said. “UNC Lineberger researchers have been involved from the beginning.”