After 16 years in Rwanda, physician and renewable energy entrepreneur Caleb King returns to his alma mater to lead the UNC Institute for Convergent Science, a partnership of the College of Arts & Sciences, the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, and Innovate Carolina.

After 16 years in Rwanda, physician and renewable energy entrepreneur Caleb King returns to his alma mater to lead the UNC Institute for Convergent Science, a partnership of the College of Arts & Sciences, the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, and Innovate Carolina.

By Logan Ward, College of Arts & Sciences

In 1999, the first time Caleb King saw Shyira Hospital in northwestern Rwanda, every window was broken. The X-ray machine was smashed to pieces. The facility had no electricity or doctors — not even beds, mattresses or blankets. Scores of patients lay on grass mats. Some were in labor. Others, feverish with malaria, were hooked to IV quinine drips.

King, a Rhodes Scholar and newly minted pediatric gastroenterologist, had traveled to Shyira after a chance meeting at a Pawley’s Island, South Carolina, church with an Anglican bishop named John Rucyahana.

Bishop John turned to his guest. “Well, Caleb,” he said. “Will you come here and work?”

King had long been drawn to international development work, but this wasn’t exactly what he had in mind. Do I have any responsibility for these people over here? King asked himself. Yes, I do.

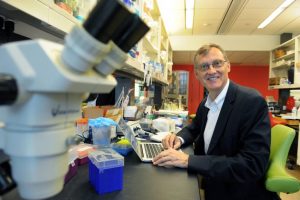

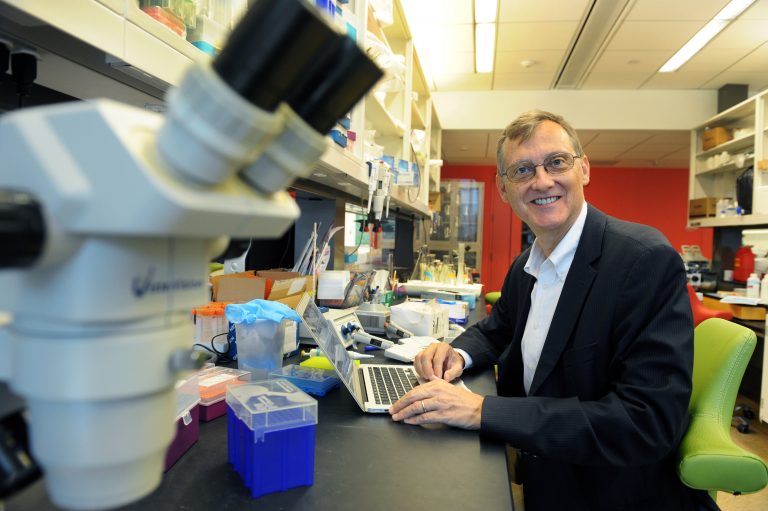

Sixteen years later, King (B.A. chemistry ’82) is back in his hometown of Chapel Hill and facing an entirely different but no less daunting challenge — leading the effort to rev up UNC-Chapel Hill’s approach to research and innovation.

This new approach, known as convergent science, is a problem-centered approach to research that breaks down academic silos and brings together unlikely collaborators. The goal? Innovation that positively impacts society, boosts value for both researchers and the University and creates jobs in North Carolina.

UNC-Chapel Hill is already a research powerhouse, conducting more than $1 billion of research annually. It is ranked fifth in the nation for federal research expenditures and 11th for sponsored research from all sources. That research has resulted in nearly 900 patents. North Carolina businesses that got their start at UNC-Chapel Hill generate nearly $11 billion in annual revenue.

Carolina scientists are already using a convergent science approach in many research endeavors, such as creating an affordable membrane-based water purification tool and replicating intricate lung tissues to model and improve treatments for cystic fibrosis.

But UNC-Chapel Hill can innovate smarter — and faster. At least that’s the idea behind convergent science. In a world facing the ravages of climate change and exploding populations in need of food, clean water and energy, maybe a guy who spent 16 years rebuilding a war-torn hospital and developing a hydropower plant to supply it with electricity is the man to lead the way.

A unicorn

Connecting with King was uncanny, said Chris Clemens, senior associate dean for research and innovation in the College of Arts & Sciences. For the past few years, the astrophysics professor has worked with Vice Chancellor for Research Terry Magnuson, Innovate Carolina and others to develop the convergent science concept. After completing a feasibility study and “innovation framework” for a new Institute for Convergent Science, the next step in turning the idea into reality was hiring an executive director.

It was a tall order. Clemens said the University needed someone who understood medicine, technology, engineering, entrepreneurship and economic development, not to mention the humanities and the workings of a large university.

“So, here comes a guy who has been a practicing doctor but who also has a Ph.D. in engineering from MIT and has been the CEO of a startup alternative energy company,” Clemens said. As a Morehead Scholar and the son of the late UNC English professor Kimball King, Caleb King has deep ties to the community. “It’s like finding the only unicorn left in the world,” Clemens added.

“The first goal of convergent science is bringing people together,” said King, a tall, thin man with an angular face, as he gazed up at the Genome Sciences Building. If all goes as planned, the Institute for Convergent Science will one day reside in a new building on the corner of South and Columbia streets, linking it with the five interconnected buildings of the Carolina Physical Science Complex. Until then, King and his team will carve out an innovation framework in this modernistic concrete-and-glass complex just south of the Bell Tower.

King entered the Genomic Café and explained how the innovation framework concept will work: Researchers will be clustered into three “lanes.” Beginning in spring 2020, ICS will pilot all three lanes in the Genome Sciences Building. Some of the space now occupied by the sunny ground-floor café will become a “research commons” representing Lane One. Academics from all backgrounds will meet to discuss problems and possible solutions. Lane Two, which will occupy a lab on the building’s second floor, represents the “NIMBLE” stage, where researchers will test novel ideas by staging demonstration projects and building prototypes. (NIMBLE stands for “New Invention — Make it Big or Leave Early.”) Lane Three, also to be housed in a second-floor lab space, will be a commercialization incubator and KickStart accelerator led by Don Rose of Innovate Carolina. There faculty will receive help with patents, startup funding and other key steps toward turning their ideas into viable businesses.

“A lot of people think you do lab research until you have an invention, and then you get it patented and raise money and start a company,” Clemens said. “That would be only two lanes.”

Providing a middle lane, King said, is crucial. “Before you have New Company, Inc., you need a space for professors and students to work together to scale up an idea and bring it up to the demonstration stage,” he added.

Like all major research universities, UNC currently engages in technology transfer. But there are shortcomings, usually involving the licensing of technology for a fee or royalty. For starters, King said that “licensing fees are more of a tax on an innovation.”

Or sometimes a company will pay a small licensing fee in exchange for the rights to an invention and then shelve the idea, often simply to quash competition. In that case, someone’s life’s work may never see the light of day.

The Institute for Convergent Science will build partnerships from the ground up, allowing researchers to maintain control of their ideas by creating their own startup companies through Lanes Two and Three of the ICS process. UNC’s Venable Hall is named for 19th-century UNC chemistry professor Francis Preston Venable, whose lab research gave birth to Union Carbide, one of the most important and profitable companies in U.S. history. The University and the state benefited from the association. But, King said, “Imagine how much more both would have benefited if the University had owned 20% of Union Carbide.”

In his bones

In many ways, King is the personal embodiment of convergent fields. He was a child of the humanities whose backyard was the UNC campus. He graduated with a degree in chemistry but decided against bench science. Instead, he directed his studies toward more practical applications, receiving a diploma in development economics from Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar, an M.D. from Harvard University and a Ph.D. in civil and environmental engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

King said he was drawn to public health and economic development. He became a medical doctor. But, he added, “I had a Ph.D. in civil engineering in my pocket and had no idea what to do with it.” He wanted to commit to work in the field, not sit behind a desk as a consultant and travel every few months to some developing country. “It was easy to see how I could be a doctor in a country in Africa,” he said. “It wasn’t as easy to see how to work as an engineer.”

That helps explain the appeal of Shyira, a hospital in need of a doctor and so much more. In 2003, King and his wife, Louise Rambo King (B.A. history ’88), also a Morehead Scholar and also with an M.D. from Harvard, uprooted everything and moved to Rwanda with their four children, ages 7, 5, 3 and 5 months. Over time, they rehabilitated the hospital, but for years the facility relied on a generator for electricity. With fuel prohibitively expensive — a gallon of gas cost around the same as 10 days’ wages — power was intermittent at best.

Fixated on solving Shyira’s energy problem, King took matters into his own hands. Through years of hard work — fundraising, engineering, negotiations with the government and even battling a corrupt business partner — King built a small hydroelectric plant to power the hospital and surrounding region.

Last spring, after his 85-year-old father died, King and his wife found themselves at a crossroads. With their children beginning to move back to the States to attend college and King’s 86-year-old mother in need of care, the family uprooted again, returning to King’s childhood home near campus. Their family had grown: About two years into their time in Rwanda, they fostered a 1-year-old Rwandan boy, whom they later adopted. He’s now a sophomore at East Chapel Hill High School.

Now King is focusing his intellect, creative energy and drive on building the Institute for Convergent Science. He’s determined to keep ICS focused on translational research — in other words, using basic science to create new therapies, procedures or diagnostic tools. “How can we address issues that are helpful to society?” he asked. “How do we develop innovation that leads to responsible development and benefits researchers and UNC, while making us a better friend to the government of North Carolina?”

He’s not starting from scratch. “There’s a culture of low stone walls at UNC,” King said. “There’s not a lot separating math from the classics or science from the humanities. There’s a real sense of collegiality here.”

Does King feel any responsibility to help UNC leverage these strengths?

Yes, he does.