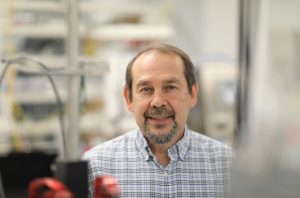

Gene therapy pioneer Jude Samulski, PhD, professor of pharmacology at the UNC School of Medicine, is featured in this NPR story about a 30-year research journey from idea to treatment reality for kids with muscular dystrophy.

This is the story of a fatal genetic disease, a tenacious scientist and a family that never lost hope.

Conner Curran was 4 years old when he was diagnosed with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a genetic disease that causes muscles to waste away.

Conner’s mother, Jessica Curran, remembers some advice she got from the doctor who made that 2015 diagnosis: “Take your son home, love him, take him on trips while he’s walking, give him a good life and enjoy him because there are really not many options right now.”

Five years later, Conner is not just walking, but running faster than ever, thanks to an experimental gene therapy that took more than 30 years to develop.

Conner was the first child to receive the treatment — a single infusion designed to fix the genetic mutation that was gradually causing his muscles cells to die. The treatment can’t bring back the cells he’s lost (he remains smaller and weaker than his twin brother, Kyle), but it has allowed the muscle cells he still has to function better.

Since Conner’s treatment, eight other boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy have received two different doses of the gene therapy. Preliminary results on six of them, tested a year after treatment, showed they, too, had improved strength and endurance at an age when boys with Duchenne usually become weaker.

The success suggests that gene therapy could be poised to change the lives of thousands of children — usually boys — who have Duchenne. But scientists still want to see the results of a much larger trial of the therapy, which is likely to begin later this year.

Conner’s parents, Jessica and Christopher Curran, never accepted the doctor’s grim prognosis. But by the time their son got to first grade, he was falling far behind his fraternal twin, Kyle, and struggling to get around the house.

“He pulled himself up the stairs,” Jessica says. “He would make it past four stairs and he couldn’t do the rest. He could not last a full day in school. The teacher would say, ‘We let him take a little nap in the classroom,’ and I’m thinking, what?”

The Currans knew that scientists were working on a treatment. About a year after his diagnosis, they’d begun to hear the words “gene therapy.”

It seemed like the answer. After all, children with Duchenne lack a functional version of the dystrophin gene, which helps muscles stay healthy. So why not fix it?

“The concept is very simple. “You’re missing a gene so you [put it] back,” says Jude Samulski, a gene therapy pioneer, founder of the UNC Gene Therapy Center, and professor of pharmacology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

Samulski devoted more than 30 years to making that simple concept work.