After being diagnosed with severe dilated cardiomyopathy, a 5-month-old infant from Brunswick County was facing an uncertain future. However, she was able to beat the odds after becoming UNC Children’s very first Berlin Heart EXCOR™ left ventricular assist device recipient – bridging her to a new heart just 11 days before her first birthday.

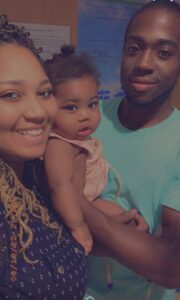

By all accounts, Alaynah Frink of Brunswick County, was a typical baby girl when she was born on August 17, 2021. Her mom, 23-year-old Amber Hewett, had a perfectly normal pregnancy and delivery. But, when Alaynah was just four-months-old, strange symptoms started to appear.

“She was throwing up really bad and couldn’t keep down any formula,” said Amber. “Her stomach was so big. She was lethargic at times, not gaining weight, not feeding well, and we could see that she was struggling to breathe. And she would let out this piercing cry. It’s a cry that a parent would never forget.”

During the month of December, Amber and Javier Frink, Alaynah’s father, continued to seek help from other medical professionals who claimed that Alaynah was in good health even though she was behind at hitting her milestones. After seeking more medical care, Alaynah was diagnosed with asthma; however, Amber’s motherly intuition still wasn’t settled.

On January 9, Amber received a disturbing call from her mother, Alaynah’s grandmother.

“She said that I need to come home now, something is seriously wrong with Alaynah,” Amber said. “My mom told me that Alaynah was going limp in her arms, projectile vomiting, and her eyes were rolling to the back of her head.”

The ambulance took Alaynah to Novant Health New Hanover Regional Medical Center, where she was admitted. After multiple tests, ultrasounds, x-rays, and bloodwork, Amber and Javier received devastating news: Alaynah was diagnosed with severe heart failure, and immediately she was airlifted to UNC Children’s Hospital in Chapel Hill, N.C.

“We were shocked,” Amber said. “We knew something was wrong but had no idea how severe it was. I didn’t know there were signs of cardiac problems that a parent should be aware of.”

“When she got to the Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (PCICU), she was stabilized medically as best as our intensive care unit and cardiology services could provide. Our entire team started to care for her very early,” said Mahesh Sharma, MD, section chief of Congenital Cardiac Surgery, and co-director of the UNC Children’s Heart Center.

Severe heart failure can cause failure to thrive. The symptoms seen in children include poor feeding, excessive sweating while feeding or playing, swelling of the feet, ankles, lower legs, abdomen, fatigue, poor weight gain, irritability and trouble breathing.

“We had to put her on medicines to help with her heart function and a breathing tube to help her body not work as hard,” said Matt Pizzuto, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics, cardiology, and anesthesiology, and interim medical director of Pediatric Cardiac ICU at UNC Children’s. “Despite that still, her heart function was very poor. Her heart had severely dilated and was stretched out.”

Alaynah was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy which progressed to cardiogenic shock, which is when the heart doesn’t deliver enough oxygenated blood to the body and some of the organs, including the kidney and liver. Alaynah’s heart was enlarged and weak, ineffectively pumping blood to her body.

“She was placed on medications for a period of time but ended up needing further support for her deteriorating heart,” said Timothy Hoffman, MD, FACC, FAHA, Governors Club Distinguished professor and division chief of pediatric cardiology in the Department of Pediatrics at the UNC School of Medicine. He is also the medical director of the Pediatric Heart Transplant program at UNC Children’s. “If all medical options are exhausted, then we consider heart transplant as the next potential therapy.”

The wait time for getting an organ is long – often more than six months. Some patients will die before a suitable heart becomes available. Alaynah’s heart was irreversibly damaged. She was facing an uncertain timeline.

“I broke down several times realizing my baby girl was in need of a new heart,” said Amber. “If I could’ve given her mine, I would have.”

“Alaynah was listed ABO incompatible which means the donor does not have to match her blood type,” said Dr. Sharma, who is also director of Pediatric Heart Transplantation and Mechanical Circulatory Support and associate professor of surgery and pediatrics at the UNC School of Medicine. “This can only be done in babies and small children, those who are typically less than one year old, since the immune system is immature. In an adult, if they received a heart that wasn’t their blood type, they would reject it immediately. However, small children do not have that strong of a response which can allow for an ABO mismatch heart to be used. This increases the donor pool and decreases wait-list mortality,” he said.

Despite Alaynah being listed for ABO incompatible heart transplant, she failed to receive a suitable donor offer. She continued to deteriorate while she was waiting. Time was of the essence.

A New Opportunity for an Artificial Heart

Alaynah was receiving maximal medical treatment, but her condition worsened. She was listed for heart transplant on January 14, 2022, but her body was continuing to shut down at an alarming rate. Because donor hearts are in short supply – particularly for infants and children – Alaynah needed something beyond medicines to keep her alive until a donor heart became available and restore blood flow to organs, such as her kidneys and liver, which were in jeopardy. She needed an artificial heart.

“That ultimately led us to think about using mechanical circulatory support, or what’s called the left ventricular assist device,” said Dr. Sharma.

The Berlin Heart EXCOR™ is a type of “ventricular assist device,” or “VAD” used to long-term support children in severe heart failure, either until recovery or until a heart transplant is possible. The device is used to take over the function of a child’s own heart when it becomes too weak to pump sufficient amounts of blood to other organs in the body.

“It’s a surgical procedure implanted to the deteriorating heart with a pumping mechanism to help the child overcome the insufficiencies of their own heart,” said Dr. Hoffman. “It’ll provide them with a normal cardiac output so that the child can rehabilitate and be in the best condition possible for a potential heart transplant,” he said.

Children have to be a transplant candidate to be offered the Berlin Heart. Some children are not candidates’ due other problems like, neurological conditions or they have a condition where they do not have a good long-term prognosis even with transplant. So, transplantation must be an option for children that receive an artificial heart.

“Alaynah underwent an extensive multi-disciplinary evaluation involving nutritionists, psychologists, cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and a whole team of professionals weighing in on her transplant candidacy,” said Dr. Sharma. “She was deemed a suitable recipient for a donor heart which made her a candidate for an LVAD.”

Dr. Sharma came to UNC Children’s from UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh where he was the director of Artificial Heart Technology. While he was there, from 2004 until coming to UNC in 2017, he had experience using the Berlin Heart, but the device had never been used at UNC.

“We have been preparing for implanting this type of device for some time, but a suitable candidate had not presented until she came along,” said Dr. Sharma.

When it was time for Alaynah to receive her artificial heart, Dr. Sharma and the team placed her on the heart-lung machine to support her circulation while working inside the heart to remove a clot and implant the device. There are two connections with the Berlin Heart EXCOR™ LVAD – one from the left ventricle where blood enters into the pump and then the LVAD pushes blood back to the body through the large blood vessel, called the aorta, which exits from the left pumping chamber of the heart. This mechanical “assistance” helps to take the load off the left side of the heart. This also helps improve the right side of her heart over time. According to Dr. Sharma the LVAD takes stress off the heart, allowing the lungs to recover, while helping to keep the patient from going into shock while waiting for a heart transplant.

On January 25, 2022, Alaynah became the first Berlin Heart recipient at UNC Children’s Hospital. It was an emotional rollercoaster for her parents, but Amber says they are so thankful for Alaynah to be put on the device.

“We stayed by her side no matter what,” Amber said. “We were not going to give up on Alaynah. We knew she was going to pull through, especially when she got the Berlin Heart.”

A Birthday Wish for a Donor Heart

Alaynah was on the Berlin Heart for 43 days. The device pumped about 214,000 times. Despite advances in technology, there are always some risks and complications associated with being on an artificial heart. Bleeding, strokes, and inflammatory reactions can occur as a result of using the device. Alaynah experienced an inflammatory response requiring medical treatment during the support period. Fortunately, her heart showed progressive recovery to the point where she was able to be “weaned” or come off the LVAD and wait for a donor heart, which Dr. Sharma says, is quite rare.

“Usually, you go straight from having the Berlin Heart to a transplant with the device in,” Dr. Sharma said. “In Alaynah’s case, we took the device out and she remained on intravenous heart medicines until it was time for a heart transplant. She was in better shape than she was when she arrived at the hospital back in January but not good enough to go home with her own heart,” he said.

On March 8, the Berlin Heart was removed, but Alaynah remained on the heart transplant list. Five more months went by as the family continued to wait for a donor heart. Alaynah had good days and bad days, but the family never gave up and still held out hope. On August 5, Amber and Javier received the news that Alaynah had a donor match for a new heart.

“In collaboration with the pediatric cardiac surgery team at Duke University, Dr. Doug Overbey and Dr. Joe Turek, were able to retrieve the donor heart for Alaynah and brought it back to Chapel Hill,” said Dr. Sharma. “Then Dr. Tommy Caranasos and I performed the heart transplant surgery on August 6.”

Alaynah received her new heart just 11 days before her very first birthday. She slowly was able to get off several medications and started showing a positive progression in her healing process.

“She’s now trying to crawl,” Amber chuckled. “Before the surgery she was wearing six to nine-month-old clothing, but now she can fit a size 2T!”

A Multidisciplinary Approach

Alaynah received her medical care from a very large team at UNC including dietitians, pharmacists, ICU doctors and nurses, cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, the pediatric heart failure team, nurse practitioners, pediatric perfusionists, child life, hematology, transplant services and so on. The pediatric ECMO team, including Wes Searcey and Janet Rudy, were helpful in managing the Berlin Heart after it was implanted. They constantly checked the device 24/7 to make sure that it was filling and emptying properly, and that no clot was forming inside the device which could have caused Alaynah to have a stroke – one of the main complications of being on the Berlin Heart. They sat by her bedside daily making sure there were no problems with the pump.

“It takes a tremendous team, and everybody has a very significant role for this to be successful for the patient and family – for them to ultimately be discharged,” said Dr. Hoffman. “We’re thankful to everyone that has been involved.”

UNC cardiologists and teammates received extensive training long before Alaynah came to UNC Children’s. Dr. Sharma said it was the dedication to provide this unique service at UNC Hospitals that allowed Alaynah the time she needed before getting a new heart.

“That’s why having the ability and expertise to use the Berlin Heart was important,” said Dr. Sharma. “We needed a team with extensive experience in implanting these devices, and we were able to build that team over the last four and half years, including the ICU, cardiology, and nutrition, and all the other key components to be able to provide this kind of care.”

“We love the medical team,” said Amber. “Everyone on the team has now become Alaynah’s best friends. She has recognized all their faces and would smile whenever they would arrive.”

UNC also had support from the Berlin Heart company who was on site when the device was implanted to assist since it was the first one at UNC. Members from Dr. Sharma’s former team at the PROCIRCA Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh also came to UNC to support the first implant.

“Alaynah also had tremendous support from her family, especially her grandmother and her mom,” said Benny Joyner, MD, chief of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. “It was an inspirational and incredible journey. It’s really a testament to how far our program has come. It reinforces how incredible our team is when it comes to pulling together to deliver true state-of-the-art care.”

And after spending 253 days in the hospital, the family can now rejoice. Alaynah was discharged from UNC Medical Center on Tuesday, September 20 to head home as a healthy baby girl with a brand new heart – a very special birthday gift.

Media contact: Brittany Phillips