Nearly a decade ago, fearing for her life, UNC medical student Tendai Kwaramba fled Zimbabwe and the ruthless regime of Robert Mugabe. Today, she’s a political refugee living in the United States, on her way to becoming a physician.

by Zach Read – zachary.read@unchealth.unc.edu

In December 2008, as Tendai Kwaramba crossed the southern border of Zimbabwe into South Africa, she wondered if she would see her native country again. She was 18 years old, had just graduated from high school, and was fleeing to the United States, where her mother, Christinah, and brother, Farai, awaited her.

The U.S. Department of State had approved her student visa and the U.S. Embassy in Harare – Zimbabwe’s capital city and her hometown – had provided documentation for her travel. But Christinah’s status with the country’s ruling political party, Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), made it too dangerous for Tendai to depart from Harare’s airport, where alert officials could detain her.

“Detainment in Zimbabwe often means death,” explains Tendai, a second-year UNC medical student who received a Master’s degree in Global Public Health from Duke University in 2015. “That’s the reality in Zimbabwe. Everyone knows someone – or knows of someone – who disappears at the hands of ZANU-PF and is never seen or heard from again.”

A Promise

To avoid scrutiny at the Harare airport, Tendai took a 13-hour bus ride to Johannesburg, South Africa, where she boarded a flight for the United States. A few weeks later, at the beginning of January, she would join Farai at Southwestern College, a small Methodist school in Winfield, Kansas.

She packed only the bare essentials for what could be the rest of her life: enough clothes for the trip and the days that immediately followed her arrival in the United States; her journal, in which she wrote poetry and documented her experiences living in hiding for the previous 15 months, outside the notice of Zimbabwean government officials; and Sudoku puzzles to occupy her time while traveling.

“I left a lot of my belongings behind,” she says. “But I brought Zimbabwean cornmeal and juice for my mom and brother – those were also essential items.”

One precious belonging Tendai carried with her, which occupied no space in her luggage, was the memory of her final visit to the grave of her father, Tinashe, who died of esophageal cancer at age 40, when she was nine years old.

“It was very difficult for me to visit his grave in the days before I left,” she reflects. “What do you say in a situation like that, at 18 years old? I told him that I loved him, that I would say hello to my mother and brother for him, and that I hoped to return to Zimbabwe to visit him again – although I had no idea if it would be possible for me to do so. I also made a promise to him that motivates me today – I promised him that I would work hard to make something of my life.”

A Role Model

Nearly 40 years ago, among native Zimbabweans, Robert Mugabe was an admired leader in the fight for Zimbabwean independence. Today, as president of Zimbabwe, he and ZANU-PF, the party he leads, are feared by many citizens – responsible for countless human rights violations, elections staged and rigged to maintain power, and a violent land-reform movement that rewarded loyal supporters and destroyed the country’s economy.

During Tendai’s high school years, Zimbabwe grew increasingly violent at the hands of ZANU-PF officials and supporters, with murders, beatings, and other forms of intimidation marring elections. Despite what felt like perpetual turmoil in the country, Tendai, who speaks several languages fluently, including her native Shona and English, received an excellent education.

“I was fortunate in that I grew up in Harare,” she admits. “Education there was fantastic, perhaps the best on the continent. English was taught from day one, and I was in school with kids from all walks of life, from up and down the social ladder. The students were very talented. Sadly, as those in my generation have grown up, they’ve been robbed of the opportunities to share those talents, and today many are jobless.”

For Tendai, it helped that her parents, both graduates of University of Zimbabwe, were well-educated and successful, despite coming from humble, rural communities that lacked the level of opportunity available in Harare. Tinashe was the managing director of a bank and Christinah taught math in primary school and high school for 21 years.

“My mom encouraged us in our studies when we were young,” she remembers. “At home, we were given advanced math assignments, levels ahead of the math we were doing in school. I was in the third grade and I recall her telling me I would thank her one day, and she was right. I’m so grateful because it made me a good student and prepared me for educational experiences throughout my life.”

Shortly after Tendai started the third grade, Christinah, who had undergone nearly two dozen surgeries on her stomach for reasons that remain a mystery today, felt a calling to join the ministry. In her spare time she began crafting and delivering Sunday sermons for the United Methodist Church the Kwarambas attended in Harare. It wasn’t long after she began preaching that they learned that Tinashe was sick.

Christinah became Tinashe’s primary caregiver throughout his illness, while also raising Farai and Tendai and maintaining her career.

“For so many reasons, my mom has been an incredible role model for me,” says Tendai, whose name in Shona means Thank you, God, for giving us a daughter. “It isn’t easy to be a woman in Zimbabwe, let alone a widow. In most cases, widows are forced to give their children to the husband’s family, and then they return to live with the family that raised them. But she told my brother and me, ‘Don’t worry – I will never give you up.’ She defied all the cultural traditions and endured all the family rifts that developed by keeping us with her.”

Closure in Zimbabwe

After Tinashe died, Christinah resigned from her teaching job and, at the encouragement of her bishop, pursued a Master’s degree in Divinity at Africa University, in Mutare, a four-hour drive east from Harare. Four years later, Christinah was pastor of a parish of 3,000 members. With Tendai at boarding school and Farai on scholarship at Southwestern College, Christinah focused increasingly on her sermons, which became known for their passion and their strong point of view.

“Anyone who has met my mom will attest that she is very opinionated,” assures Tendai, laughing.

In 2007, ahead of the next year’s elections, opposition supporters were being targeted and intimidated by ZANU-PF officials and supporters across the country, and Christinah took notice. One July morning she delivered a fiery sermon to her parishioners.

“The theme was, ‘Where there’s no vision, people will perish,’” shares Christinah. “It was given in response to the events in our country. It was one of my best sermons, and many people in our church were happy about it.”

But not everyone was pleased. Some in the audience interpreted her words as a challenge to the country’s political leadership. The following morning she received a visit at the parsonage from two ZANU-PF officials.

“We’ve come to take you to the presidential office in Harare,” they told her as she met them in the driveway.

Christinah understood exactly what that meant. As a pastor, she had comforted many families whose loved ones had been taken away in the middle of the night, never to be seen or heard from again. She told the men that it was her duty as pastor not to leave the parish without notifying the community of her whereabouts. Fortunately, she found the parish school headmaster nearby. He sensed the seriousness of the situation and insisted on traveling with them to Harare. The men prohibited him from riding in the same car with them, so he followed them in his car.

In Harare, Christinah was taken to the top floor – floor 18 – of the presidential building. More than a dozen men awaited her in the room. They’d placed a chair for her to sit in, in the center of a circle of chairs.

“These were big, fierce men,” she says. “I hadn’t been around men like them before. I could tell that they were violent. I could smell the blood on them. They told me I’d been summoned by the highest person in Zimbabwe, the one I despised in my sermon.”

They interrogated her, questioned why she would preach against the man who fills the people’s bellies with food and sends the country’s children to school, and demanded that she defend her sermon; instead, she preached it to them, just as she had to her parishioners the previous morning.

“For some reason, I wasn’t scared in the moment when I delivered my sermon to them,” she says. “I believe it is because the headmaster knew where I was. If I were to disappear, Farai and Tendai would know what happened to me. Thanks to this selfless man, they’d have closure, which gave me strength in that moment. Not having closure is terrible for so many of the families I counseled as a pastor.”

After she preached to them, the men threatened her life, showed her the various ways they penalized those who dissented against Mugabe, and warned her never to give another sermon like that again. Then, 12 hours after they’d picked her up in Mutare, she was taken to the ground floor of the building and pushed outside into the darkness, where the headmaster waited for her on the sidewalk near his car.

“I’ve never seen a man who could risk his life like that,” she says. “By standing outside and refusing to leave, they knew that he would know what happened to me if I never came out, so they let me go.”

Our People

Over the next several days, Christinah processed what had happened to her and what her future held. ZANU-PF officials had taken all her identification and gotten the names of all her family members, including Tendai, her mother and father, and her 10 siblings and their families. Her bishop asked her to consider staying on as pastor in the parish, but inevitably ZANU-PF would find fault in one of her sermons – she wouldn’t be as lucky the next time they came for her.

She called Tendai home from boarding school the weekend after her detainment to explain the situation.

“I was 16 years old,” says Tendai. “I told her, ‘You’re going to die. They’re going to come back for you. They don’t let people go after things like this.’”

As Christinah considered what to do next, she received a letter in the mail from SMU’s Perkins School of Theology. SMU had heard about her. She’d been the best student at Africa University, a school funded by the United Methodist Church, and she had experience leading parishioners. Would she be interested in applying to SMU for graduate work, with the possibility of enrolling in August 2008 or January 2009?

The following August was more than a year away. She was now on a ZANU-PF list. As time passed, her risk of another visit by ZANU-PF would only increase. With the elections coming the next year, she was certain to be targeted.

She called Farai, who urged her to accept the offer from SMU. Farai then spoke with Bishop Richard Wilke, the Bishop in Residence at Southwestern College who, with his wife, Julia, funds scholarships for international students at at the school. A widely known leader in the Methodist community, Bishop Wilke drove with Farai from Kansas to SMU to meet with the admissions team, which agreed to accept Christinah early.

“Bishop Wilke asked SMU if I could come immediately and fill out my application when I arrived, and SMU said ‘Yes,’” Christinah recalls. “I didn’t have a dime to my name – they even paid for my flight.”

Six weeks after her detainment by ZANU-PF, Christinah was on a flight to Dallas, where she would begin her graduate studies in Pastoral Care at the Perkins School of Theology.

“My family and I owe Bishop Wilke and all the institutions that have helped us our lives,” Christinah says. “They are our people.”

In Hiding

With another year of high school remaining, Tendai didn’t qualify for a student visa to leave Zimbabwe with Christinah, so they planned for her to stay at her boarding school until she graduated. Then, hopefully, she could attend college in the United States. Bishop Wilke, meanwhile, lobbied U.S. Senator Pat Roberts and other Kansas representatives to expedite approval of a student visa for Tendai.

After living years of my life that weren’t so happy, and that were troubling, I wanted to be somewhere that emphasized the importance of being happy and that developed well-rounded physicians. – Tendai Kwaramba

As pending elections increased turmoil in the country, ZANU-PF officials visited individuals on their list. Christinah’s old parish received a late-night visit. When officials discovered that the pastor was not Christinah, but a replacement, and that Christinah had fled, they sought out Tendai. They went to her school, but the school’s headmaster wouldn’t share a list of his students.

“Leaving my daughter in a country that was after me – and that would likely try to get to me through her – was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do,” Christinah says. “I cried day and night at SMU. I saw how people were being massacred during that time. They were the bloodiest elections in the world.”

To evade detection, Tendai moved in with friends of Christinah’s, to their farm in the remote countryside outside Mutare. The family could not be easily connected to Christinah. Tendai also switched schools to a multiracial private school without a connection to the church. No one at the new school knew her. Christinah’s SMU community raised funds to help pay Tendai’s tuition.

“It was hard,” Tendai says. “You’re a teenager, and you feel invincible – like no one will get to you. You’re also at this rebellious period of your life when you don’t want to be told where you can go and what you can do, but you’re confined to a house, to a property, and you’re not allowed to leave except to go to school.”

Tendai passed the time by doing schoolwork, reading, writing poetry, and helping the family with chores on the farm.

“I like to say that I could tend to pigs now if I had to,” she says. “I could get a plot of land and do some of my own farming after that experience.”

She became close with the family and their children. In one defiant moment, however, she wanted to travel with them on a trip they were making to Harare. They explained the danger both she – and they – would be in by taking her, and they reminded her of the promise they’d made to Christinah, whom they regularly spoke with by phone from third-party phone numbers, away from their house. But they couldn’t fend Tendai off, and they relented.

“We had almost made it home from Harare,” remembers Tendai, “and I was feeling like I’d been proven right that we’d be fine, when suddenly we ran into a ZANU-PF checkpoint. As we began inching closer to officials, we argued about whether I should stay in the car or get out of the car. I realized that I’d been wrong to travel with them and that I was putting them in danger, so against their wishes, I ducked down, crawled out of the car, and hid in a nearby ditch. Fortunately, I wasn’t discovered, and about two hours later they returned to get me.”

15 Seconds

Tinashe loved to take his family on trips. They traveled together to South Africa, Zambia, Namibia, and Kenya. But he loved traveling in his own country even more.

“Zimbabwe is such a beautiful place, with a lot of history,” Tendai says. “One of his favorite spots to take us was Victoria Falls.”

Parts of North Carolina remind Tendai and Christinah of Zimbabwe – the hills around Chapel Hill, the lush green of the trees during the summer time. At UNC, Tendai is also reminded of the challenges she and her family have been through. She had several options to choose from for medical school, but UNC was the right fit for her because it was the antidote to those difficult memories.

“I chose UNC because I knew I’d be happy here,” she says. “After living years of my life that weren’t so happy, and that were troubling, I wanted to be somewhere that emphasized the importance of being happy and that developed well-rounded physicians. Grades and tests are important at UNC, of course, but when I interviewed, students talked about the other things that interested them and how they make time to explore those interests. You’re here for four years – it should be a place you love to be.”

Although Tendai is deep into her second year of medical school, forming bonds with classmates and preparing for her board exams, she often thinks of her father. Last year, during the social medicine course taken by first-year students, students were asked to write a personal illness narrative. She focused on Tinashe.

“I took a chance with it,” says Tendai, whose paper was submitted for – and won – the Alan W. Cross Social Medicine Paper Award.

The essay reexamined an experience she had with her father when she was eight years old, two years into his illness. They were home together one afternoon while Christinah was still at school and Farai was away at boarding school. As Tendai walked past the bathroom, she noticed her father sitting on the bathroom floor. He had thrown up. Vomit was visible on the side of the toilet and the floor.

“He hadn’t made it in time,” she says. “I stopped, we looked at each other, and I ran to my room and closed the door. I didn’t stop to help him and I didn’t try to clean up. It was a 15-second interaction, and it’s something I remember so vividly today.”

In her room, she cried.

“I didn’t understand why I was crying,” she continues. “Today, the moment remains difficult for me because I turned away from him, without helping. I was eight years old, I felt awkward, and now I understand that I wanted to rid myself of that awkwardness.”

In her paper, Tendai reflects on how illness is processed differently by people in Zimbabwe, especially men, who try to pretend that nothing is wrong, that everything is normal, and that things will be okay.

“My father and I never once talked about him being sick,” she says. “It was just something that was there, and we never spoke about that moment when I saw him. He tried not to show vulnerability and wanted to do all the things that he would do if he were healthy – take me to school, and so on. In some ways that was good, but I think I would have processed his illness better as I grew up if we’d talked about it.”

When caring for patients as a physician one day, she hopes to draw from what she learned from his illness.

“I think it’s important to have those conversations with your kids,” she says. “Kids see things even if they don’t understand and compute them at the time. They see that something is changing, and I saw that, for sure, but we never really discussed it.”

During the past two years, Tendai has considered what she might specialize in. Last summer she traveled to Brazil through the UNC School of Medicine’s Office of International Activities. It was her second trip to Brazil – her first came during graduate school at Duke. She worked on a research project at Hospital de Cancer de Barretos, in Barretos, Sao Paulo.

“It’s a private cancer center where Brazilians receive free care,” she says. “When I first learned about it, it sounded too good to be true. But it was as advertised – it’s a wonderful place – and I was able to have a diverse clinical and research experience looking at cervical cancer, HPV, and racial disparities.”

She presented her research at the Global Health and Noncommunicable Diseases conference in Atlanta in September 2016 and at UNC’s John B. Graham Student Research Day two months later – and she returned to the United States with improved Portuguese-language skills.

The trip also reinforced her interest in oncology as a specialty – an interest that doesn’t surprise Christinah.

“Tendai has wanted to be a doctor since she was a little girl,” says Christinah. “She was always with me while I was taking care of her father. For a long time she talked about being a heart surgeon, but now she talks about helping people with cancer. I think she’s inspired to provide the help to patients that her father couldn’t get in Zimbabwe.”

Point of Need

“In colonial Zimbabwe, when my mom was born, you had a better chance of going to school if you had an English name, which is why my mom was named Christinah,” says Tendai.

Last May, nine years after arriving in the United States, Christinah completed a long educational career, which includes a Master’s from Perkins and a PhD in Pastoral Care and Counseling from Texas Christian University.

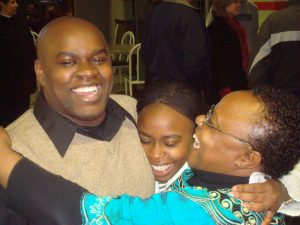

“I call her Dr. Mother now,” laughs Tendai, who flew to Texas to celebrate with Christinah, Farai, and the other program graduates.

Today, Christinah does supervisory training in chaplaincy at Texas Health Harris Methodist Hospital, in Fort Worth. She trains chaplains in visiting patients, grief counseling for families, and baptizing stillborn babies.

“The hospital setting is where people are most vulnerable,” says Christinah. “Because of our story, I wanted to meet people at their point of need, when the world seems to be at the end, when cancer is at stage 4 and we are facing death.”

Tendai sees Christinah’s current role as the perfect fit, bridging her two passions: “She combines both her worlds – she was a teacher for 21 years and now she can teach, but she also gets to do the work of a chaplain.”

During Tendai’s first year of medical school, Christinah and Farai traveled to Chapel Hill to witness the annual White Coat Ceremony, a tradition that marks the first time medical students don their white coats. As Tendai walked onto the stage to receive her coat, Christinah could be heard ululating across the auditorium. The sound, mhururu, is an expressive form reserved for women. It signifies “what one has endured to get to this point,” Christinah says.

“It was an emotional moment,” recalls Tendai. “There was definitely some embarrassment when she did that in front of so many people, but it was a moment I knew my mom was completely happy, and it felt like everything – terror, fear, loss – was worth it.”

Meanwhile, Farai, whose name means Thank you, God, for giving us a son, has completed his PhD in chemical engineering at Oklahoma State University, and today he is a chemistry professor at Sterling College in Kansas.

Despite their successes in the United States, the Kwarambas still miss Zimbabwe. Tendai and Farai have nieces, nephews, and friends’ babies who have been born that they’ve never met, and they’ve become estranged from family with whom they were once close. Tendai and Christinah, unlike Farai, were designated a political refugee, which means they cannot return to Zimbabwe. They keep in touch with family and friends by phone as often as they can. But they’ve also found family at each of her stops in the United States.

“I’ve encountered a different set of challenges here, but I’ve been fortunate to meet kind people living in Kansas and while at Duke and UNC,” says Tendai. “Friends here have become family.”

In 2011, Christinah was unable to attend her mother’s funeral because of her status in Zimbabwe, but she holds out hope of returning one day. She continues to speak out against the current regime, which is controlled less and less by Mugabe as he ages, but which remains under ZANU-PF’s rule. She is one of several African theologians who have addressed the U.S. Congress about Zimbabwe and its challenges and opportunities.

Their success as a family fills many who have gotten to know them with joy. Bishop Wilke, whom Farai still visits in Kansas, recalls when Farai first set foot on campus and how he learned more about the threats facing his mom and sister.

“We’re in awe of Christinah, Farai, and Tendai,” Bishop Wilke says. “We really are. We were able to help in some ways, but these are three brilliant people with advanced degrees who are headed toward making major contributions to our country. They’ve carved their own path since arriving here, and we’ve been so fortunate to get to know them and to be a part of their experience.”