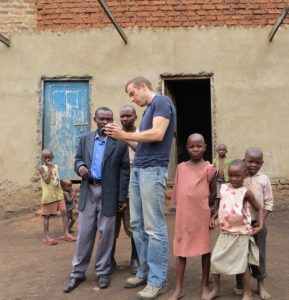

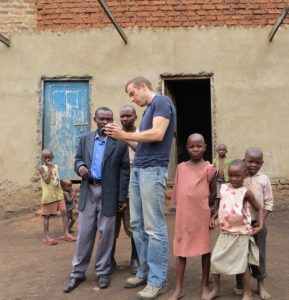

Ross Boyce, MD, MSc, an instructor in the division of infectious diseases, draws on his military experience to provide care and help overcome access issues in rural Uganda. He has been awarded a Challenge Grant by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to support his work.

Ross Boyce, MD, MSc, an instructor in the division of infectious diseases, draws on his military experience to provide care and help overcome access issues in rural Uganda. He has been awarded a Challenge Grant by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to support his work.

By Jamie Williams, jamie.williams@unchealth.unc.edu, 984-974-1149

Cliché be damned, Ross Boyce has built actual bridges. During his second tour of duty in Iraq, Boyce served as a civil affairs officer, working with a team of soldiers and engineers helping to build and repair infrastructure ravaged by war.

“I was running a budget with millions of dollars, repaving roads, building sewer systems, health clinics, irrigation systems for farms, repairing broken pipes, whatever needed to be done,” Boyce said.

He remembers 22-hour days working on project proposals, coordinating logistics, talking to local leaders about their needs and how the U.S. military could help meet them.

“Counterinsurgency is not traditional war in terms of battle lines and uniforms,” Boyce said. “In a lot of ways it’s just good community policing, what was called ‘winning the peace.’ You get out, talk to people about what’s going on, and maybe you notice a road that’s broken down, or a pipe that burst, and we go back in and fix that.”

This was Boyce’s second tour. On his first, he served as commander of a reconnaissance platoon in Eastern Baghdad, seeking out enemy fighters to help his unit plan their next movements.

“We would go out and look for the insurgents,” Boyce said. “Usually you find them by walking down the street and getting shot at.”

Boyce had originally planned to go to medical school directly after graduating from Davidson College. But in his junior year, he decided to change plans.

“I suppose being 21 years old and facing four more years in the classroom wasn’t particularly exciting so – much to my parents’ chagrin – I decided to put medical school on hold,” Boyce said.

He received his commission as an infantry officer.

“If you’re going to be in the Army, I think there is a certain appeal to being at the tip of the spear,” Boyce said.

During that first tour, Boyce was honored with two Bronze Stars, including one for valor in combat.

When he returned from Iraq the first time, he enrolled at the UNC School of Medicine. Between his second and third years of medical school, several of Boyce’s friends were being redeployed as part of the troop surge. He volunteered to go back to Iraq. He earned another Bronze Star during that second tour.

His work as a civil affairs officer sparked an interest in public health, so after graduation from the UNC School of Medicine, he earned his MSc from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Following that, he went on to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) for an internal medicine residency.

At this point, Boyce thought his career would lead him to service in an around combat zones. But, while he was at MGH, he decided to visit their partnership site in Uganda. The trip would change the course of his life and career.

“Well, that first trip, I met my future wife and fell in love with Uganda,” Boyce said.

His now wife, Raquel Reyes, MD, MPA, was then directing MGH’s partnership site in Uganda.

As Boyce was exposed to the health needs in Uganda, he also began to shift the idea he had for his career.

When I got to Uganda I saw the medical wards filled with kids sweating and sick with malaria and I thought ‘this is what I should be doing,’” Boyce said.

Boyce and Reyes then came to UNC. She works as a hospitalist, and the two closely collaborate on international development and research efforts, recently forming an NGO to support the development work in Uganda.

Now Boyce’s work in Uganda is based in malaria research but goes far beyond that, as he studies geographic and other barriers to care.

“This is the end of the road,” Boyce says of rural Uganda. “How can we provide care to people at the last mile?”

Boyce works in the highlands of Western Uganda, near the border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. His home base is the Bugoye sub-county, which sits at the base of the Rwenzori Mountains.

“These are not the Appalachians,” Boyce says laughing. The extreme elevations and steep hillsides provide challenges to the people who live here. Challenges that Boyce is looking to overcome.

“If you live way up in the mountains, getting down to the health center is what we might consider a weekend hike,” Boyce said. “Just think about having to carry a sick child down a mountain. That is what originally sparked my interest in how terrain can affect medical care.”

That interest has grown to support a range of research, including a new project recently awarded a Grand Challenge Grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. This award comes with $100,000 of initial funding and 18 months to show results. After that time, projects are reevaluated and Boyce will be eligible for additional funding of up to $1 million.

Boyce, in collaboration with Paul Delamater, PhD, from UNC’s Department of Geography, will analyze where people are coming from to get their children vaccinated. They will use software to map where these people live and analyze it in comparison to people seeking care for malaria and prenatal services.

“If we see 100 people coming from one village and only 10 coming from another, it’s an opportunity to improve services there and also do a little more digging to find out exactly why they aren’t coming. Is it just distance, or is it some sort of fear or cultural attitude?” Boyce said.

According to Boyce, around 50 percent of Ugandan children receive the standard package of vaccinations and even fewer receive them on time.

“We are going to triangulate this data with data on people seeking prenatal services and malaria care so we can see where the gaps overlap,” Boyce said. “The next step will be to take services to these people. There are outreach events now, but they are essentially blind, you just pick a location and go without any data to back it up. I’m interested in better targeting so we can get to the people who need us the most while using resources most effectively.

When you only have so many resources, you have to prioritize, that’s the overriding philosophy of the work that I do.”

He uses the skills he gained in the military to seek and solve problems. He walks the hills, talks to his local collaborators and keeps an ear to the ground. He understands the limitations of his environment and works to find solutions that can be effectively put in place and sustained.

“The main health center where I work is led by someone with training equivalent to a PA,” Boyce said. “There is no doctor on site. There is an assistant PA, a few nurses, and midwives, but they cannot even perform cesareans. There is an inpatient clinic, but that is primarily filled with kids with malaria. If you need a higher level of care, that’s 45 minutes on the back of a motorcycle.”

That inpatient clinic full of kids stricken with malaria influences one of Boyce’s research projects – examining the efficacy of the rapid diagnostic test used to diagnose malaria. His concern is not that they don’t work well, it’s that they often lead to over diagnoses and, in this resource limited environment, a waste on the supply of medications available.

The tests are antigen based, and the antigen that is tested persists for 40 days if there is an infection. So, in most cases, long after the person has successfully been treated. If a child returns to the clinic, later in the same month for example, there is an extremely high likelihood of a false positive.

“Malaria is incredibly common, so if a child has 4 or 5 bouts of malaria in a year, they would test positive for almost an entire year,” Boyce explains. “There are tons of reasons why a child would have a fever, but if they are constantly treated for Malaria, how much medication is being wasted and, more importantly, what issues are we missing?”

For those that do need care for Malaria, HIV, or anything else, Boyce is also working on a system to more efficiently distribute the medications, acknowledging the incredible barriers that stop people from coming to the health clinic. This work closely aligns with the project he will be researching surrounding vaccines. He’s mapping the routes people take to get to the clinic for their medication and exploring options like a subscription service that will pay a local resident to make deliveries via motorcycle.

“I’m not a brain surgeon. A lot of what I do is about basic logistics,” Boyce said. “Every time I go to Uganda I see something else that we could be doing. Then, the question is, how can we make it better? I have my own expertise in infectious disease and public health, but this is relentless and nonstop. Soon we’re going to need a lot more help.”