Dr. Sriram Machineni joins the UNC department of medicine’s division of endocrinology and metabolism to build a chronic care model for treating obesity.

By Kim Morris, UNC Department of Medicine

The State of Obesity’s 2017 report shows North Carolina has the 16th highest adult obesity rate in the nation, now at 31.8 percent, up from 20.9 percent in 2000, and from 12.3 percent in 1990. Obesity causes or worsens a multitude of diseases like type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, and arthritis, conditions that not only impact health, but also quality of life and place a huge burden on healthcare systems.

For people affected by obesity, the options for weight loss are vast and confusing. Most programs only talk about short term results, rarely do they talk about two year results, usually because people regain the weight they lose. A chronic care model with a multi-modality patient care approach can offer an alternate way to address obesity and its consequent co-morbidities in a population.

“Traditionally, we’ve put too much emphasis on poor habits as the only cause for obesity,” says Dr. Sriram Machineni, who recently joined the division of endocrinology to build a multi-disciplinary clinical and research program. “In many cases, we need to think about biology, not only behavior, to take a different approach. If a treatment doesn’t work, it can mean the body’s biology is not responding and a change in the type of treatment may be required.”

Machineni’s research interests lie in the variability of patient response to obesity treatments, and the development of personalized obesity treatment strategies that incorporate genetic, metabolomic, and microbiota signatures, as well as socio-economic factors. “The components required to make this possible are all here at UNC, but we need to find a way integrate them to produce a scalable and sustainable solution,” said Machineni.

Prior to UNC, Machineni completed an obesity medicine fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School where he served as a faculty member for four years. In addition to treating patients at the MGH Weight Center, Machineni studied energy balance and body fat regulation in preclinical models, allowing him to interpret clinical research findings and patient response to treatment in the context of the underlying biology.

A Referral Pyramid that Starts with Primary Care

As director of UNC’s Medical Weight Program, Machineni draws on his primary care physician experience, prior to obesity medicine training. During that time he first realized that weight management was largely ignored by primary care providers, including himself, despite being fully aware of the impact of obesity on a multitude of diseases. “I didn’t have anything more to tell my patients than to eat less and exercise more. If they came back and said it didn’t work, I didn’t have anything else to offer them, other than asking them to try harder, suspecting that they were not doing enough.”

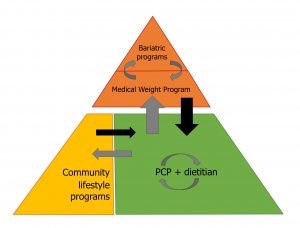

At UNC Health Care, Machineni envisions a broad-based, sustainable population approach that trains primary care physicians in obesity medicine, so that only the sickest and the most complicated patients get referred to a tertiary care center for obesity management, much like the model for diabetes management.

“Ideally, programs in the community would take care of the lower risk patients, and as their risk becomes higher, with medical problems, they would get referred up to a center, for more intensive therapies going up to surgery, if necessary. To make obesity care scalable, we could introduce a clinician, who has an interest in treating obesity to act as the obesity medicine champion for each of the primary care practices.”

The referral pyramid starts with every primary care practice providing initial phases of treatment with integrated referral resources, such as dietitians. Patients needing more intensive lifestyle-based education and support would be referred to lifestyle community programs. If the treatment approach is unsuccessful, patients would then be referred to a specialized medical weight program that works closely with bariatric surgeons. Patients seen in the specialized program would get treatment, and after being on a stable regimen, return to continue the management from the primary care office. This will allow patients to get the frequent contact and support that they need for better long-term outcomes in an environment that is familiar to them. The idea is to get the referral from primary care providers, provide appropriate treatment and then get patients back to primary care for long-term follow up and maintenance.

“This integrated structure doesn’t exist anywhere, and so far, the referral up has only been for surgery. Most often only one program tries to take care of all patients with obesity, leaving many sick patients on long waiting lists.”

Rethinking Obesity, A Paradigm Shift in Education

For the referral pyramid to be successful and sustainable, education is needed to enhance engagement by the primary care community and overhaul the way the healthcare system approaches obesity. In his “rethinking of obesity,” Machineni wants to work with primary care providers to help them understand the biology of weight regulation, to help them engage patients in a broader range of treatments, which is a necessary paradigm shift for obesity care.

“Obesity is not like pneumonia. It does not go away when we treat it. Instead, it’s like diabetes or high blood pressure that you have to treat long term. Once weight is controlled, we have to continue the treatment to have long term success. Because when treatment stops, weight gain usually occurs.”

UNC Health Care’s Medical Weight Program features a research program with clinical trials to study investigational weight loss medications and an education program to train providers, in addition to the clinical program for the management of obesity. The clinical approach is based on leveraging variability of response to treatments and the use of multiple modalities as appropriate for the health impairment caused by the individual’s obesity. The overall strategy builds on resources already present in the UNC medical community, to move towards a truly integrated program for the local patient population. Learn more here: UNC Medical Weight Program.