Using a custom-built exposure chamber, UNC School of Medicine and EPA scientists tested consumer-grade masks and improvised face coverings to show how effective they can be at protecting individuals from airborne particles of similar size to those carrying SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

CHAPEL HILL, NC – It’s been shown that when two people wearing masks interact, the chance of COVID-19 transmission is drastically reduced. This is why public health officials have pleaded for all people to wear masks: they not only protect the wearer from expelling particles that might carry SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19), but masks also protect the wearer from inhaling

particles that carry the virus. Some people, though, still refuse to wear a mask. So UNC School of Medicine scientists, in collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency, researched the protectiveness of various kinds of consumer-grade and modified masks, assuming the mask wearer was exposed to the virus, like when we interact with an unmasked infected person.

Published in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, the research shows that some masks were as much as 79 percent effective at blocking particles that could carry the virus. These were masks made of two layers of woven nylon and fit snug against the wearer’s face. Unmodified medical procedure masks with ear loops – also known as surgical masks – offered 38.5 percent filtration efficacy, but when the ear loops were tied in a specific way to tighten the fit, the efficacy improved to 60.3 percent. And when a layer of nylon was added, these masks offered 80 percent effectiveness.

“While modifications to surgical masks can enhance the filtering capabilities and reduce inhalation of airborne particles by improving the fit of the mask, we demonstrated that the fitted filtration efficiencies of many consumer-grade masks were nearly equivalent to or better than surgical masks,” said co-first author Phillip Clapp, PhD, an inhalation toxicologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the UNC School of Medicine.

Co-first author Emily Sickbert-Bennett, PhD, director of infection prevention at the UNC Medical Center, added, “Limiting the amount of virus is important because the more viral particles we’re exposed to, the more likely it is we will get sick and potentially severely ill.”

As the adoption of face coverings during the COVID-19 pandemic became commonplace, there was a rapid expansion in the public use of commercial, home-made, and improvised masks which vary considerably in design, material, and construction. There have been a number of innovative “hacks,” devices, and mask enhancements that claim to improve the performance characteristics of conventional masks – typically surgical or procedure masks. Despite their widespread dissemination and use during the pandemic, there have been few evaluations of the efficiency of these face coverings or mask enhancements at filtering airborne particles.

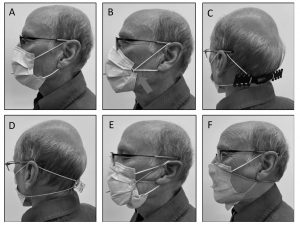

In this study, the researchers used a recently described methodological approach based on the OSHA Fit Test to determine the fitted filtration efficiency (FFE) of a variety of consumer-grade and improvised facemasks, as well as several popular modifications of medical procedure masks. Seven consumer-grade masks and five medical procedure mask modifications were fitted on an adult male, and FFE measurements were collected during a series of repeated movements of the torso, head, and facial muscles as outlined by the OSHA Quantitative Fit Testing Protocol.

Here are the different mask types with filtration efficacy. Bolded below is the top-of-the-line N-95 mask, which proved to be 98 percent effective.

Consumer-grade facemasks:

2-layer woven nylon mask, ear loops, w/o aluminum nose bridge: 44.7%

2-layer woven nylon mask, ear loops, w/ aluminum nose bridge: 56.7%

2-layer woven nylon mask, ear loops, w/ nose bridge, 1 non-woven insert: 74.4%

2-later woven nylon mask, ear loops, w/ nose bridge, washed, no insert: 79%

Cotton bandana – folded Surgeon General style: 50%

Cotton bandana – folded “Bandit” style: 49%

Single-layer woven polyester gaiter/neck cover (balaclava bandana): 37.8%

Single-layer woven polyester/nylon mask with ties: 39.7%

Non-woven polypropylene mask with fixed ear loops: 28.6%

Three-layer woven cotton mask with ear loops: 26.5%

Medical facemasks and modifications:

3M 9210 NIOSH-approved N95 Respirator: 98%

Surgical mask with ties: 71.4%

Procedure mask with ear loops: 38.5%

Procedure mask with ear loops + “loops tied and corners tucked in”: 60.3%

Procedure mask with ear loops + “Ear Guard”: 61.7%

Procedure mask with ear loops + “23mm claw hair clip”: 64.8%

Procedure mask with ear loops + “Fix-the Mask (3 rubber bands)”: 78.2%

Procedure mask with ear loops + “nylon hosiery sleeve”: 80.2%

Other authors are James M. Samet, PhD, MPH, Jon Berntsen, PhD, Kirby L. Zeman, PhD, Devrick J. Anderson, MD, MPH, David J. Weber, MD, MPH, and William D. Bennett, PhD.

This study was supported by the Duke-UNC Prevention Epicenter Program for Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections and a cooperative agreement between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Media contact: Mark Derewicz, 984-974-1915