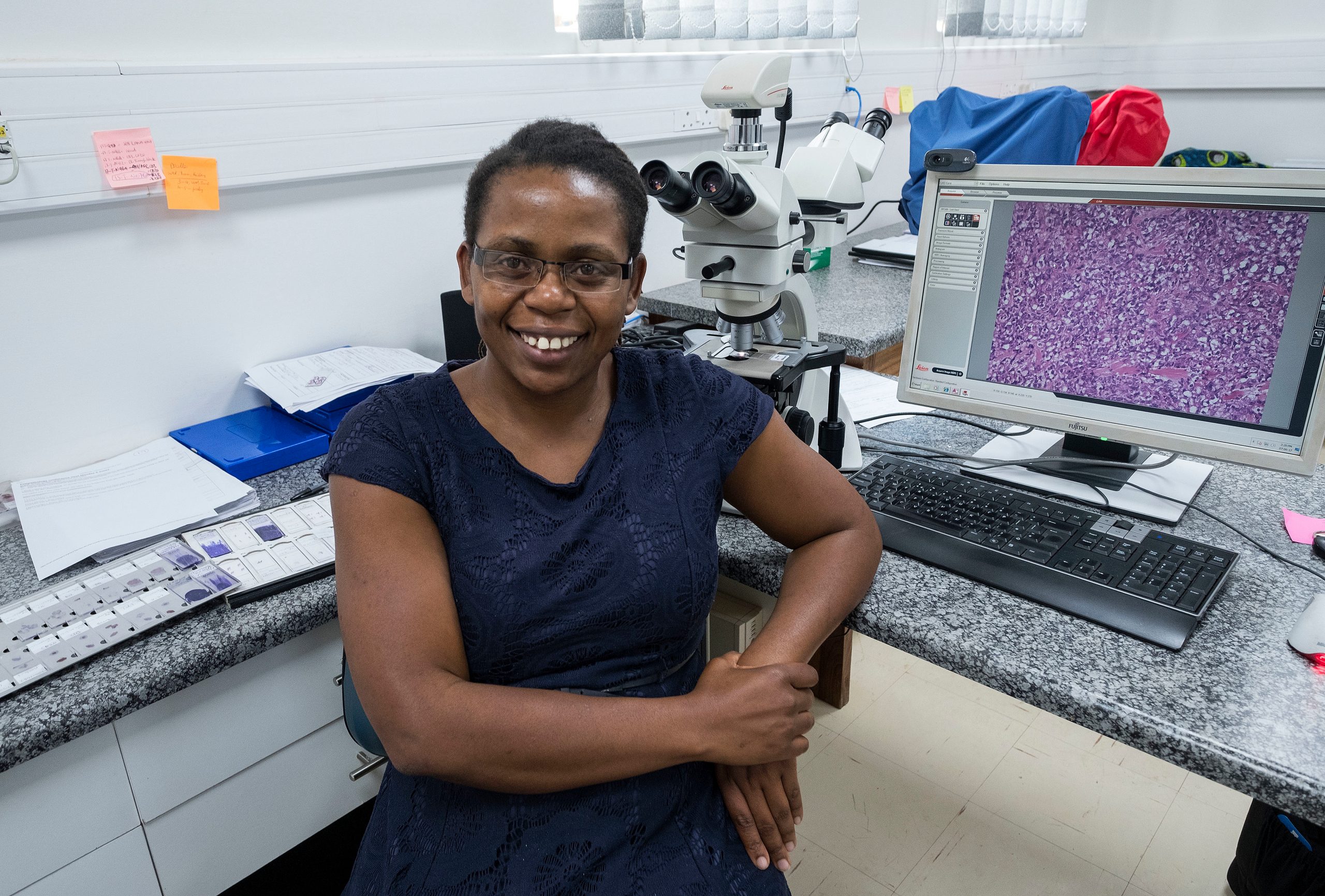

Program staff Tamiwe Tomoka (at microscope) and

Edwards Kasonkanji (standing)

By Jamie Williams, jamie.williams@unchealth.unc.edu, Photos by Jon Gardiner

From his window at UNC Project-Malawi, Satish Gopal, MD, MPH, has a clear view of the cancer hospital currently under construction on the campus of Kamuzu Central Hospital. The metaphor isn’t lost on him or anyone else there.

For the past five years, since moving his family to Lilongwe, Malawi, Gopal has worked with many partners to build a cancer care infrastructure in this country. First, he set out to convince international partners that the rising cancer burden in sub-Saharan Africa represents the next great global health crisis. Then, he set out to show that people with cancer could be treated in this low-resource environment. He’s still progressing on that front, but the hospital coming out of the ground just outside his window is a sign of just how far the program has come.

Of course, he’s not alone in this mission, and he gets a bit irritated by the suggestion that fostering the training and career development of the Malawian members of his team is merely ‘important.’

It’s vital, he says. Imperative. Important doesn’t even come close.

“The only way to make these programs work is to be on the ground, actively partnering, identifying research priorities, identifying the most promising young clinicians and investigators and helping them propel their careers forward, Gopal said. “Because of that approach we are scientifically productive, but also valued as a key partner in moving cancer care forward in Malawi.

“This is how global health should be done.”

His team includes Dr. Tamiwe Tomoka, the first female pathologist in Malawi. Dr. Lameck Chinula is the only surgeon in Lilongwe able to perform a radical hysterectomy to treat cervical cancer, which is diagnosed in high rates in Malawi. Dr. Agnes Moses is a seasoned infectious disease researcher, leading studies in HIV-related malignancies in Malawi. These leaders and a rising cohort of Malawian physician scientists represent the “cream of the crop,” Gopal says.

And this week, they will have the opportunity to showcase their work, as the team welcomes partners from across the country and the world to Lilongwe for the Malawi Cancer Symposium.

Across two conversations, both in Lilongwe, and back in Chapel Hill, Gopal, a UNC Lineberger member and Cancer Program Director for UNC-Project Malawi, took time to discuss the current and future state of cancer care in Malawi.

Q: You have lived with your family in Malawi for five years but come back to Chapel Hill for rotations each year. Why do you think it’s valuable to see patients in both locations?

Part of what I like about going back and forth is having both perspectives, which I find valuable. But it’s definitely an adjustment. In some ways, it’s amazing how little time we spend [in the US] talking to patients. You’ll be talking about a patient right outside their room with 10 doctors from various specialties, all basing the conversation on what you’ve seen on a computer. I find that striking. In some cases, you could get the information you’re looking for by just posing a simple question to the patient, but it’s almost like we try to get there by any means other than that.

Taking care of patients in Malawi is the exact opposite. You have to rely on your hands and your brain. And, frankly, that doesn’t feel great either. It would be nice to have more data available. I often feel like I’m trying to make the best decision I can with partial information. You compensate for that by talking to patients, spending time with them, and using that information to try and get a sense for what’s happening.

Q: You’ve compared the state of cancer care in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2017 to the understanding of HIV around 2000, where do you see the parallels?

People need to be reminded that the huge evolution in HIV treatment has occurred in a relatively short amount of time. If you think back just 15 years, there was no effective treatment available for HIV in parts of the world most affected. And the academic community, along with international advocacy organizations, led the way with a lot of proof of principle-type studies that showed life-saving treatment could be delivered even in African villages. At the time, there were legitimate – not fringe – academic discussions where people were questioning whether or not it was possible to actually treat HIV in Africa. People said the regimens were too complicated, there were too many pills. You heard people saying things like ‘African patients from rural areas don’t have watches, how will they know when to take their pills?’

So I think on some level people just had to get engaged and do really well-designed small clinical studies – what we would call Phase I or Phase II studies – to show that the HIV treatment adherence and outcomes in Africa were the same as they were in the US.

And so now, in terms of treatment, everyone knows antiretrovirals work, and it’s in many respects just a matter of delivery. To a large extent, it’s become an economic and implementation exercise.

For cancer, we’re like HIV back in 2000. There’s a lot of cancer. Or rather it seems like there’s a lot but we’re not really sure because the surveillance and measurement isn’t that great. But we are asking and working to answer the same questions those HIV researchers were working on: can it be treated here? Can it be treated the same way here as in the United States? If not, what needs to be changed? What can we expect the outcomes to be?

Q: What were some early lessons learned through your foundational cancer work?

It’s clear that standard chemotherapy regimens can be administered in Malawi. When I got here, I really wasn’t sure whether we would be killing people with chemotherapy and that’s clearly not the case. But, there is certainly a limit to the intensity of treatment that can be delivered. Some of the more complicated infusion regimens we give routinely in the U.S. are just not practical.

The construction of the cancer hospital is a great step forward, but we won’t be offering stem cell transplants in Malawi any time soon, possibly not in my lifetime. However, we do have the opportunity to think about cancer care differently. Could we develop new treatment methods and take chemotherapy out of the equation? Those are the types of questions that will be relevant to cancer care in North Carolina and across the world. It’s reverse innovation in a way.

Q: What about patient education and raising the public awareness of cancer?

There is a lot of misinformation that patients receive in their home communities. So raising public awareness requires educating, and there is still a lot of work to do in that area. But, you can have sensible conversations with patients. They may be very poor and live in circumstances much different from the patients in the United States, but they understand that they are sick and if the information is presented to them appropriately, they can certainly participate in decision making surrounding their own care.

Q: What are some of the unique aspects of UNC’s cancer work in Malawi that you are excited to highlight at the Malawi Cancer Symposium?

A lot of people are interested in our pathology work, which we are doing extremely well. Generally, the comprehensiveness of our work is unique. There’s truly basic, clinical, and public health work, reflecting the tremendous breadth of our Lineberger Cancer Center in Chapel Hill. That’s really exceptional in a region that is simply littered with one-off cancer studies. We have an increasingly diverse funding portfolio. People are starting to take notice. When people think about emerging cancer work in this part of the world, we are a group that gets thought of, and I hope that continues.

Q: Are young Malawians becoming more interested in going into the field of cancer research?

I think it is seen as a large unaddressed public health need and an area where you can make a really big impact. On our team now, we really do have the most talented minds in the country. These are Malawians who have been sponsored to leave their country for training and have chosen to come back despite more lucrative opportunities elsewhere. These are the people who will become regional and international leaders.

Tamiwe Tamoka leads our pathology lab and recently gave a talk at the National Cancer Institute about pathology capacity building. Our AIDS Malignancy Consortium participation is led by Lameck Chinula and Agnes Moses. Lameck just received an African Cancer Leaders Award from AORTIC (African Organization for Research and Treatment in Cancer). That’s all really exciting. It is common for our funders and collaborators to comment on our amazing team of Malawians. That really distinguishes the entire philosophy of the UNC-Project.

There are other research groups in the country, but I don’t know that any of them have the track record for producing Malawian doctors and researchers that we do.

It is incredibly important to me to see the excitement our staff has when they are accepted into a PhD program with a full scholarship or when they get a paper published. For me personally, that is so rewarding and a nice antidote to the many difficulties and challenges we face here.

Q: Does having Malawians in these forward-facing leadership positions help to build trust, and help to justify the government investing in the new cancer hospital?

I think the fact that UNC has been in Malawi since the ‘90s says a lot about the leadership, mission, and vision of the program. All of those values are shared by our cancer team. But, we don’t have a right to be here. The government could tell us tomorrow, ‘UNC, you are no longer welcome in our country.’ So, we have to earn trust every day. I think the way that we have gone about this, the inclusive way we’ve welcomed anyone with an interest in our work, and the constant engagement with the Ministry of Health and the College of Medicine makes all of this work.

The theme of ‘us versus them’ is the dominant theme of international politics at the moment. When something goes wrong it’s easy to blame outsiders. But UNC is seen as a trusted institution in Malawi. From its inception, the program has been a collaboration between UNC and the ministry. It’s a very integrated model and that helps break down that ‘us versus them’ dynamic. It requires daily caretaking. When people don’t feel like the patients are being taken care of properly, or they don’t see Malawians advancing their careers, the mentality creeps back in. But right now the Ministry sees UNC as their primary partner on cancer and we work every day to continue to earn their trust.

Q: Along those same lines, what would you say to people who would question UNC and Lineberger’s investment in cancer care in Malawi?

Obviously the top priority of UNC is service to the people of North Carolina. But maybe that’s not ambitious enough. There are ways for Lineberger to have impacts on individual patient’s lives internationally and generate science that is globally informative. That happens in Chuck Perou’s lab in Lineberger, and it happens in a clinic room in Lilongwe. We have a unique opportunity to learn something new and exciting about why cancer occurs and how it can be treated.

I know some would make the argument that until everyone in North Carolina is cured of cancer, we shouldn’t spend a dollar on international work. I’m clearly on the global side of the global versus nationalist argument. I’ve moved my entire family to Africa and we’ve lived here for eight years. The more we can all learn from each other, the closer we can work together, the larger the impact that we can make. In HIV, some of the science generated in Malawi has changed international treatment guidelines. I’m convinced we can do the same for cancer. We can change the way lymphoma is treated in Chapel Hill with studies done in Malawi. That’s why I’m here.