CHAPEL HILL, NC – A new study by UNC School of Medicine researchers shows that e-liquids are far from harmless and contain ingredients that can vary wildly from one type of e-cigarette to another.

“We found that e-liquid ingredients are extremely diverse, and some of them are more toxic than nicotine alone and more toxic than just the standard base ingredients in e-cigarettes – propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin,” said study senior author Robert Tarran, PhD, associate professor of cell biology and physiology and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. “The FDA, which helped fund our study, is just beginning to regulate e-liquid ingredients, and we hope that our data will inform their efforts.”

The study, published in PLoS Biology, comes as e-cigarette use becomes more popular, particularly among teens and young adults. Recent surveys suggest that roughly 15-25 percent of American high school 11th and 12th graders have used e-cigarettes. Other surveys showed that 10-15 percent of American adults have used the products. These numbers rise every year. Yet so far there have been few studies on the health effects of vaping.

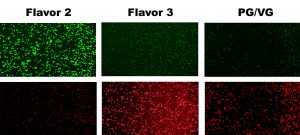

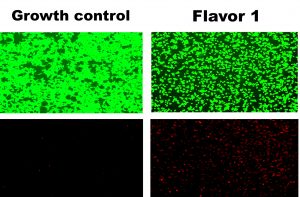

Tarran and colleagues, including co-first author Flori Sassano, PhD, research project manager in the Tarran lab, developed a system for the rapid evaluation of e-liquid toxicity, based on a standard toxicology approach. Their system uses large plastic plates arrayed with hundreds of tiny indentations, or wells, in which fast-growing human cells are exposed to different e-liquids. The more these liquids reduce the cells’ growth rates, the greater their toxicity.

E-liquid’s main ingredients of propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin have been considered non-toxic when delivered orally, but of course e-cigarette vapors are inhaled. The UNC scientists found that even in the absence of nicotine or flavorings, small doses of these two organic compounds significantly reduced the growth of the test cells.

Besides these base ingredients, e-liquids include small amounts of nicotine, plus flavoring compounds, and are sold under names such as “Candy Corn,” “Chocolate Fudge,” and “Berry Splash.” The scientists tested a proof-of-concept sample of 148 e-liquids and also performed a standard gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis of the ingredients. They found that these ingredients varied tremendously across the e-liquid products tested, and on the whole, more ingredients meant greater toxicity.

The greatest toxicity effects came from two flavor compounds, vanillin and cinnamaldehyde, which have been widely used in e-liquids.

“The higher the concentrations of these compounds in particular, the more toxic the e-liquids were,” Sassano said.

The toxicity results remained largely the same when the researchers used other cell types, including human lung and upper airway cells. Toxicity results were also the same when the researchers exposed the cells to vaporous puffs of e-liquids, which is how the cells would be exposed when an e-cigarette user inhaled the vapor. These experiments confirmed the reliability of using standard toxicology cell cultures and e-liquids in liquid forms as a relatively fast initial screening method.

“We have this tool and it’s very fast and reliable, and we now plan to use it on a wider scale,” Sassano said. “There are more than 7,700 e-liquid products out there, and regulators as well as ordinary people should know more about the ingredients they contain and how toxic they might be.”

To aid in disseminating such results, Tarran, Sassano and their colleagues have set up a database of e-liquid ingredients and toxicity data at www.eliquidinfo.org.

The other co-first author of the study was undergraduate researcher Eric S. Davis. Tarran and Sassano, as well as other co-authors Bryan Zorn, UNC research specialist, and Matthew Wolfgang, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology, are members of the UNC Marsico Lung Institute. Other authors include Gary Glish, PhD, professor of chemistry, and graduate students James Keating and Tavleen Kochar, all in the UNC College of Arts and Sciences. Tarran is the director of the UNC Center for Tobacco Regulatory Science and Lung Health.

The National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration funded this research.