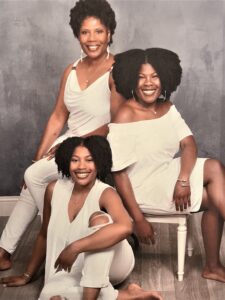

Sydney and Sheridan Taylor of Durham, North Carolina, have lived with this rare genetic disorder all of their lives. They and their mother, Helena, recount how far they have come and what more needs to be done during pain crises and emergency visits.

Sydney Taylor, a 25-year-old nursing student from Durham, was getting ready for work one July morning when exhaustion set in fast, and pain then raged through her body, the telltale signs of a sickle cell pain crisis.

She quickly contacted her supervisor at one of her two part-time jobs, explaining that the combination of Carolina heat, a busy schedule, and the impending stress of a new semester were causing her condition to flare. She needed to miss work that day and likely the next day to make a full recovery.

Her supervisor’s response: We need you tomorrow. Sydney, realizing the importance of listening to your body, took off work anyway. She knew what might happen if she pushed herself too hard. And she also knew her supervisor might not ever understand the degree of her pain and exhaustion.

Sydney’s condition has been invalidated numerous times throughout her life, especially in emergency rooms and classrooms. Sickle cell disease is painful, plain and simple. If more people are more understanding of the invisible illness, they could be treated earlier and avoid emotional turmoil, as the lives of the Taylor sisters demonstrates.

Unfortunately, awareness of the painful reality of sickle cell disease is lacking. UNC Health and the UNC School of Medicine are trying to change that.

What Causes Sickle Cell Disease

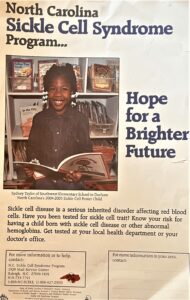

Sickle cell disease, also known as sickle cell anemia, is an inherited red blood cell disorder predominantly affecting African Americans and Hispanics, with many patients knowing a family member who also has sickle cell disease. Rarely, this disease affects Caucasians. It affects about 7,000 to 10,000 people in North Carolina.

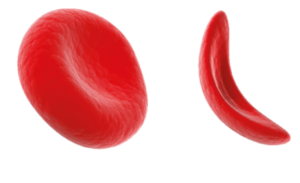

Patients with sickle cell have abnormally shaped red blood cells that prevent blood from reaching the body’s tissues and organs. The affected blood cells resemble the curved blade of a sickle, causing them to interlock and form “traffic jams” in the blood vessels. This results in anemia, debilitating pain, fatigue, and other serious health problems.

Although sickle cell disease is not as well funded or researched as other chronic illnesses, a few medical advancements have been made over the years to treat the disease. But, despite such accomplishments, there remains a general lack of understanding among the public and medical professionals on how sickle cell disease presents and the measures that need to be taken in the case of emergency situations, such as pain crises.

A Shocking Diagnosis

Helena Taylor, a 56-year-old woman from Durham, knows this all too well. In 1998, she gave birth to her first daughter, Sydney, at UNC Hospitals. A few days after birth, Helena learned that her daughter had been diagnosed with sickle cell disease. She was confused and shocked.

Sickle cell disease occurs when both parents carry an abnormal allele in a gene that regulates hemoglobin in the body, termed sickle cell trait. It is found during a simple blood test. Helena knew that she had sickle cell trait because she went through routine blood testing during her time in the Navy. Her ex-husband, who had served in the Air Force for ten years, was never informed that he had the trait.

If both parents have the sickle cell trait, there is a 25% chance that any child of theirs will have sickle cell disease.

“All I knew about sickle cell disease is that it could mean a life of despair,” said Helena.

Helena became pregnant with her second child, Sheridan, four years later. The parents knew there was a chance her second baby could still have sickle cell. When she was five months pregnant, Helena was asked to undergo a procedure in which a doctor draws blood from the fetus’s umbilical cord for testing. It came back positive for sickle cell disease and both parents decided to go forward anyways.

“We chose to still go forward with the pregnancy because her life was worth living just as much as anybody else’s life,” said Helena. “We, then, had to prepare ourselves for having not one, but two children with the disease.”

A Life After Diagnosis

From the very beginning, Helena and her ex-husband have been heavily involved in their children’s healthcare. They’ve driven them to dozens of doctor’s appointments, taken turns driving and staying with them in emergency room visits, and documented their resiliency and struggles with sickle cell disease. And they continue to be there for them to this day.

Sydney was a poster child for sickle cell in the state of North Carolina from 2004-2005. Both Sydney and Sheridan were featured in UNC Children’s annual calendar in 2012. They also participated in a video for UNC Children’s Hospital with Dr. Rupa Redding-Lallinger, MD, their long-time pediatric hematologist-oncologist, who has since retired.

“I want new families who have children with sickle cell disease to see that there is a life after this diagnosis,” said Helena. “And your child still has the ability to succeed in all facets of life.”

This is apparent when it comes to the lives of these two sisters, who have triumphed.

Sydney and Sheridan, Soaring High

Sydney, now 25-years-old, has a bachelor’s degree in English and comparative literature with a minor in women’s and gender studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is currently attending nursing school at North Carolina Central University, while also working part-time at a hotel and a retail store, both located in Durham.

She now takes an oral medication called hydroxyurea that prevents pain crises and reduces the need for blood transfusions. Although issues arise every once and a while, Sydney has felt that taking her medicine and knowing her triggers have kept her condition under control.

A few things can act as “triggers” for sickle cell patients, including dehydration, physical exercise, cold weather, and even excitement. But Sydney emphasizes that sickle cell presents in patients in many different ways, and that more people with the disease are living longer life spans that rival that of those who do not have the disease.

“Everybody’s experience with sickle cell is different, and that involves the type of care that they receive, too,” said Sydney. “I always get an ‘I’m sorry’ when I share that I have sickle cell because many people still think that it is a death sentence. But having this disease is not a death sentence.”

Sheridan, now 22, is majoring in mass communications at Meredith College. While maintaining the status of a full-time student, she also works the early morning shift as a customer service agent at RDU International Airport. She is incredibly passionate and committed to doing what she wants when she wants to do it, says her mother, Helena.

Sheridan’s lifelong battle with sickle cell disease has taught her the value of perseverance. In May, she was wrapping up preparations for an exciting study abroad trip to Japan, plans that took a whole year to put together. A pain crisis emerged, seemingly out of nowhere, in the middle of the night. The experience made her re-evaluate her plans for Japan.

“I had everything planned out, but my sickle cell is the one thing that kept me from doing it,” said Sheridan. “It’s something no one has control over. But, it’s important to know when to listen to your body. Sometimes you have to let go of something that you want to do for the sake of remaining healthy.”

Sickle cell disease is not common in Japan. If Sheridan were to have another unexpected pain crisis abroad, she might not get the care that she needs and her life could be at risk. Nevertheless, she is still committed to studying abroad. With the support of her hematologist, Sheridan’s sights are now set on London. Her hematologist has made mention of collaborative efforts with a colleague in the London area, should Sheridan pursue her studies in that area.

Pain Crises Illuminate a Need for Education, Understanding

Since turning 18, Sydney and Sheridan have had to become self-advocates for their health. The journey has been a steep learning curve, from navigating MyChart to selecting providers and speaking up for themselves in doctor’s appointments, emergency rooms, and in-patient settings.

Their mother is confident that her daughters will never allow their conditions to be discounted, but there is concern about the times when Sydney and Sheridan are unable to advocate for themselves while under disorienting medications, and their parents are not present.

Sheridan’s recent pain crisis, the one that subverted her trip to Japan, occurred in the middle of the night at her father’s house. She sat in the emergency room for two and a half hours, her pain level rising from ten to an excruciating twenty. While the emergency doctors were well-versed in a variety of illnesses, they were not giving her the appropriate type of pain medication, nor were they administering an appropriate dosage to control her pain.

Sheridan was hospitalized for seven days because of the severity of her pain crisis. It was the longest she has ever had to be hospitalized. Sydney has had similar experiences as well.

Unfortunately, many members in the sickle cell community have been labelled as drug addicts, or drug seekers, due to them asking, and needing, stronger pain medications than the average patient. The Taylor family understands that for Sydney and Sheridan, Dilaudid, or hydromorphone, is the only medicine that is most effective for their pain management.

They understand that it can only be given in certain doses, they only ask that emergency physicians follow the action plan and recognize their pain as valid.

“So much needs to be done to educate staff who work in doctor’s offices, hospitals, and emergency rooms,” said Helena. “It would be nice if there was more consistency with providers following patient action plans. Instead, they have to recreate the wheel while my children are experiencing extended periods of pain and suffering unnecessarily.”

Looking Forward

Sydney’s experiences with sickle cell disease continue to fuel her passion for nursing. Throughout her clinical rotations, she has received numerous compliments from patients and nurses about her approach to patient care. She has taken an interest in oncology and women’s health, owing to her own familial history with cancer and sickle cell disease.

With her London trip peering over the horizon, Sheridan is tasked with taking it easy and keeping a close eye on her health. But, tenacious as always, that doesn’t stop her from living her daily life.

“Although the pain may be chronic, the world doesn’t really stop for you,” said Sheridan. “You have to know how to work with what you are dealing with, go back out, and do everything that it is you need to do.”

Media contact: Kendall Daniels, Communications Specialist, UNC Health | UNC School